به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

The Iranian Revolution at 30

by Homa Katouzian

22-Feb-2009

Lecture delivered at University of Amsterdam, 20 February 2009

Thirty years ago the Iranian revolution overthrew the Pahlavi monarchy in Iran. It subsequently became known as the Islamic revolution, although it had a much wider base than that, and it was only its further developments that led to the Islamic revolution.

The shah believed that he was highly popular with his own people, an illusion which was both due to the rapid increases in the standards of living and the fact that his system did not allow any criticism, least of all of his policies, to be made by anyone however high in society. He would therefore gauge his relationship with the people from sycophantic reports and stage-managed demonstrations of public support on certain occasions. His greatest tragedy, thus, was that he became a victim of his own propaganda.

The Politics of elimination

The politics of elimination had begun with the 1953 coup. Within two years after that coup, the communist Tudeh party and the democratic National Front had been eliminated from Iranian politics. The relatively gentle elimination of some of the loyal but independent-minded members of the regime later in the 1950s – for example, General Zahedi, Ali Amini and Abolhasan Ebtehaj– did not amount to a major change in the nature of the regime although it indicated the trend towards further concentration of power. This was also true of the increasing coolness of the relationship between the shah and the religious establishment from the mid-1950s. The power struggles of 1960-1963 could either result in a less dictatorial government within the existing system if Ali Amini or the second National Front had got the upper hand, or in absolute and arbitrary government, if the shah had managed to outwit them, as he in fact did. The shah then jettisoned any vestige of independent, though still very loyal, advice by men like Hossein Ala, Abdollah Entezam, Qa’em Maqam al-Molk, etc., etc., indeed the whole of the conservative establishment who had given him support through and after the 1953 coup, and who had ties with the religious establishment in Qom, Tehran, Mashahd and elsewhere. It was not so much the land reform alone that led to the great disenchantment of these groups, since its first stage, passed by Amini’s land reform law - though more genuine and less in the landlords’ favour than the second stage - had not led to an open confrontation by them. Much more provocative than land reform was the shah’s assumption of total power and the elimination of the political establishment from politics in the wake of his White Revolution.

The bazaar and the urban crowd had a far greater role than the land owning class in the revolt of June 1963, even though land reform did not threaten their interests at all. Even the students joined the demonstrations. Indeed in a published statement Ali Amini who was no friend of landlords condemned the way the revolt of June 1963 had been suppressed, and this led to a government order confining him to the city of Tehran.

The second National Front had not been an effective movement despite the widespread support that it had enjoyed at the time of its formation in 1960, largely as a result of the public good will towards Mohammad Mosaddeq. By 1964 it had completely run out of steam and was under heavy criticism from its own members such as the student movement and other Popular Movement organizations. The coup de grace was delivered by Mosaddeq himself who was drawn into the controversy by the critics and wrote highly critical letters about the Front’s ineptitude from his country residence to which he was forcibly confined by the government. The Front leaders resigned en masse and Mosaddeq gave the green light for the formation of the third National Front. This organization eventually came into being in 1965. Times however had changed and the shah would no longer tolerate so much as the existence of such moderate, open and peaceful organizations which could do little more than publishing critical leaflets and holding private meetings at their homes. From now on there had to be no dissenting voice of any kind.

The politics of elimination thus spelt doom for open, liberal and democratic movements, which, outside of the Tudeh party, had occupied the sphere of political opposition since Mosaddeq. In this way the field became wide open for guerrilla campaigns which began to take shape almost immediately after the onslaught against the democratic parties. Indeed the fiery and idealistic young people – mostly university students and graduates - who began to turn to violent solutions started by putting the blame for failure on democratic leaders themselves for choosing peaceful rather than violent tactics in their political struggles.

Society versus the State

The politics of elimination had a dialectical effect. While it led to the elimination of conservatives, liberals and democrats from politics, it encouraged the development of its opposites, namely beliefs, ideologies and movements which, one way or the other aimed at the overthrow of the regime and the elimination of the shah himself.

Many of the most secular intellectuals – virtually all leftists, and most of them Marxist-Leninists – began to discover the virtues of the county’s religious culture and traditions, decry Weststruckness, and advocate cultural authenticity and ‘nativism’. The terms gharbzadegi and gharbzadeh (variously translated, respectively, into Westoxication and Wetoxicated, Weststruckness and Weststruck, etc.) which the writer and intellectual Jalal Al-e Ahmad had used to attack the cultural and politico-economic influence of the West became everyday words used by members of virtually all classes to denounce state projects and decisions as well as anyone or anything they did not like.

The General Discontent

The revolution had many long and short causes, although it would not have turned into the revolt of the whole society against the state had the state enjoyed a reasonable amount of legitimacy and social base among some – at least the propertied and / or modern – social classes.

A major consequence of high, sustained and steady economic growth rates which were generated by increasing oil revenues was the rise of new classes in the society amid a high population growth rate. There thus developed a large community of traditional classes with good or reasonable standards of living and modern education, and a new sense of social confidence, which regarded the state as alien and oppressive. And large numbers of their young people adopted revolutionary attitudes, joining, supporting or at least applauding guerrilla activities and any other action against the regime. They believed, as did virtually all other opposition groups, that the regime was in the pockets of the West, and therefore extended their anger against it to western countries, especially America which was its strongest ally and had a considerable presence in the country.

However, the state’s biggest failure from the point of view of its own interest was that it alienated the modern social classes as well, at least some of which should have formed its social base. That would have been the case if the regime had been a dictatorship instead of a one-person arbitrary rule (estebdad), since it would have involved the participation of a political establishment in the running of the country, with the dual advantage of the regime benefiting from some critical discussion and advice, and the opposition not being blanket and comprehensive. Apart from that, the opposition would have faced not just one person, but a whole spectrum of ruling people who, when the chips were down, would have rallied round and defended the regime in their own interest.

Increasingly, not only traditional propertied classes, and not just the growing modern middle class professionals and middle income groups, but even modern propertied classes who owed much of their high fortunes to oil and the state were alienated from the regime. They did not have any independent economic and political power, and were critical of some of the economic policies of the state without there being a forum or channel for airing them. No criticism of the regime, however mild and well-intentioned, would in any case be tolerated, even if expressed in private. This was the greatest single grievance of intellectuals, writers, poets, journalists, etc., against the regime. Censorship was very strong, but, as noted, any verbal criticism, if reported, would also be duly punished.

The oil revenue explosion of 1973-1974 ironically had very negative consequences for the regime. It greatly enhanced its sense of self-confidence, and led to greater repression and a more arrogant attitude and behaviour towards the public. More than that, the economic consequences of the new oil bonanza and the political decisions to which they led resulted in widespread public indignation. The quadrupling of the oil prices almost immediately led to a massive increase in public expenditure, including the doubling of the expenditure estimates for the fifth economic plan. As both state and private incomes rose sharply so did consumption and investment expenditure, fuelling demand inflation. At the same time since the supply of many products ranging from fresh meat to cement could not be sharply increased from the domestic sources, supply shortages developed in the midst of financial plenty. Imports could not relieve the situation adequately partly because they would take time to deliver, partly because (as in the case of fresh local meat) imports were not possible, but mainly because of limits to port as well as storage and transport facilities, which could only be extended in the long run.

The general rise in prices had other consequences for spreading anger among important social classes such as traders, merchants and business people. While, as noted, excessive state spending was the principal cause of rising inflation, it blamed it on hoarding and profiteering on the part of producers, wholesalers and retailers. Prices of a number of commodities were reduced by fiat. A public campaign was launched against ‘profiteering’ (geranforushi), involving thousands of young men as agents of the official Rastakhiz party who were sent to the bazaars, shops and other business premises to find the culprits and take swift administrative measures against them. Hundreds of merchants and traders, including one or two leading businessmen, were arrested. Others were fined. Shops were closed down and trading licences were cancelled. This did little to relieve the inflationary pressures, but it spread and intensified anger among the business community, both traditional and modern. Nor did it satisfy the ordinary public who came to see merchants and businessmen as scapegoats for the state’s arbitrary policies.

Given the state and scale of discontent among the various classes and communities of the society briefly described above, it is not surprising that the revolution proved to be so widespread when it came. Still, the protest movement would not necessarily have resulted in a full-scale revolution, had the state responded to its earlier stages differently than it did.

The protest movement

It is always difficult to discover with certainly the origins of any revolution. The origin of the February 1979 revolution is sometimes put as far back as the coup d’etat of August 1953. But in fact many things might or might not have happened between 1953 and 1979 which could have avoided the revolution, the larger factors being the revolt of June 1963, the rise of the shah’s arbitrary rule, and the quadrupling of the oil prices in 1973-74 which further enhanced the arbitrary power of the state and led to misguided economic policies. Thus the long-term origins of the revolution may be said to go back to the 1960s when the upper and modern social classes were eliminated from politics; and the short-term factors stemmed from the explosion of oil revenues which led to the intensification of absolute and arbitrary rule, with the result that, as noted above, virtually the whole of

the society became alienated from the state.

Ironically, it was President Carter’s election in November 1976 and the Iranian regime’s quick response to it which helped to launch the protest movement. For a decade already, evidence of severe human rights violations had been slowly building up in the reports of such important Western human rights organizations as Amnesty International as well as the press and media.

Amnesty’s first major report on Iran which closely documented widespread legal violations and human rights abuses was published in the same month that Jimmy Carter was elected president. In February 1976, a detailed article on torture on Iran appeared in Index on Censorship, the reproduction of excerpts from which in New York Times had a significant impact on the wider political circles in America. A major foreign policy point of Carter’s campaign was his emphasis on human rights. The main targets were the Soviet Union and other socialist countries, but also some Latin American countries, e.g. Nicaragua, whose illiberal regimes had been traditionally backed by US administrations. However, Carter did not pass any public comments on the human rights situation in Iran, either then or later when he became president. The shah, on the other, hand, did not have good memories of Democratic presidents such as John Kennedy and generally regarded Democratic administrations as being critical of his regime.

The inauguration of President Kennedy in 1960 had prompted the shah to allow for a certain amount of liberalization which had been followed by the power struggles of 1960-1963, ending with his assumption of total power. His immediate response to Carter was similar. Early in 1977, he announced the end of torture in Iran, and by August of that year he had pardoned 357 political prisoners. And although censorship of the press was still very strong, it became possible to publish articles, for example, on the difficulties faced by Iranian agriculture.

All this was seen by the opposition as a sign of the shah’s weakness, almost literally believing that he had been ordered by Carter to relax his regime, though their analyses of the possible causes of this was varied and typically fanciful. They talked about ‘the change in the international atmosphere’, meaning the attitude of America towards the shah’s regime. Thus emboldened, on 13 June 1977 the Writers’ Association which had never had the right to function normally issued an open letter demanding basic rights. Signed by forty writers, poets and critics, it was addressed to Prime Minister Hoveyda and asked for official permission to open a public office for the Association. This was followed on 19 July by another open letter on the same theme, signed by ninety-nine authors. Shortly before this, a group of prominent advocates had signed a public statement demanding the return of judicial power and status to the law courts.

Within a couple of months a number of political and professional associations were reconstituted or came into being. Almost all of these organizations had liberal-democratic tendencies, asking for freedom of expression, the enforcement of the county’s constitution, the return of judicial processes, etc. They did include both leftist elements and Islamic views, but until after ‘the Poetry Nights’ of November 1977, the far left and the Islamist movement – which later set the goal of overthrowing the regime – were still in the background.

Feeling the pressure from without and within, in August the shah dismissed Prime Minister Hoveyda’s cabinet, making Hoveyda himself minister of the royal court. Meanwhile there had been a series of demonstrations and strikes at universities throughout the country, which was to increase in extent and frequency as the movement continued. The campaign for freedom and human rights, still short of a general call for the overthrow of the regime, peaked during the ten nights of poetry reading sessions, held in November, at the German cultural centre, the Goethe Institute, and Aryamehr technical university. Attended by thousands of people, they were organized by the Writers

Association and became known as The Poetry Nights, until the tenth night when they were broken up by the police.

Also in November, the shah paid a state visit to the United States, and while he was being welcomed by President Carter on the lawns of the White House, Iranian students demonstrating against him clashed with a small number of his well-wishers, and the police firing tear gas resulted in the shah, Carter and their suite to appear weeping live on television. Viewers also heard the slogan ‘Death to the shah’ for the first time, being shouted by the demonstrators outside the White House, before it became a regular slogan in the streets of Iranian cities less than a year later. The shah returned to a warm but officially organized welcome, and a few weeks later Carter celebrated the New Year as the shah’s guest in Tehran. Both in Washington and in Tehran, the president was fully supportive of the shah, emphasizing Iran-American friendship and cooperation.

Revolution

Until then the campaign had had more of the character of a protest or reform movement, although there certainly were revolutionary forces ready to come forward at the right moment. The first such opportunity was offered by the official vilification of Ayatollah Khomeini in the press. Earlier, the Ayatollah had issued a statement from his place of exile in Najaf ( Iraq) attacking the shah, calling the shah a servant of America, and saying that the Iranian people would not rest in their struggle against his regime. Signed under a pseudonym, the article against him was published on 7 January 1978 in the leading semi-official daily Ettela’at against the best judgement of its editor who feared a strong public reaction. It described Khomeini as an agent of both Black (i.e. British) and Red (i.e. Soviet) imperialism, ‘an adventurous cleric, subservient to centres of colonialism’.

The reaction in Qom was swift and angry. Copies of the newspaper in which the article had been published were torn and burnt. The religious colleges and bazaar were shut down. There were public clashes with the security forces, and an attack on 9 January on the headquarters of the official Rastakhiz (Resurgence) party led to civilian casualties, the official figure being two dead, the opposition figures, 70 dead and 500 injured.

On 19 February 1978, the ritual 40th day of the mourning for those killed in Qom, there were vast demonstrations in Tabriz, most of whose people were followers of the moderate Grand Ayatollah Shariatmadari, the senior marja’ in Qom. Once again, clashes with the security forces led to bloodshed and widely different figures for the dead and wounded were quoted by the government and the opposition. In turn, the 40th day of the dead of Tabriz resulted in demonstrations and bloodshed in various cities, and thus the 40-day cycle became a familiar event in the revolutionary process.

Qom, then, was the first major turning point. The second major turning point of the revolution occurred on 19 August 1978. The Cinema Rex in Abadan – Iran’s oil capital – was set ablaze by unknown arsonists resulting in the death of 400 and more people inside. The crime was never fully investigated either before or after the revolution and it is not known who or what the culprits were. But the state got the blame, partly as a matter of course, and partly because it had been putting out propaganda that the opposition were utter reactionaries, opposed to all things modern, including cinemas. The public then believed that this was done by the state to blame it on the opposition and prove their point.

The third major turning point came on 8 September, subsequently dubbed Black Friday. Four days before, the great Islamic festival of Fitr, concluding the month of fasting, had been celebrated by tens of thousands of people in a mass prayer held in the streets of Tehran, led by a revolutionary cleric. This was followed the next day by a demonstration of a crowd of more than a hundred thousand people who for the first time shouted ‘Say death to the shah’. A huge rally was called for Friday 8 September in Tehran’s Zhaleh Square (Friday being weekend in Iran) but the night before martial law was declared in Tehran and 12 other cities and all public meetings were banned. It is likely that, as it was said at the time, the public did not receive the news of the new measures in time. At any rate, an anticipated huge crowd gathered in Zhaleh Square at the appointed time and were told by the general administrator of martial law to disperse. When they refused, and after a round of warning shots in the air, the soldiers fired into the crowd.

There was a lull for a couple of days but street clashes often resulting in bloodshed were soon resumed, massive demonstrations (sometimes by one or two million people) were organized, and there were political strikes by industrial workers, oil company workers and employees, the press, National Bank and other government employees, eventually embracing virtually every profession. At one point judges and the whole of the department of justice also went on strike.

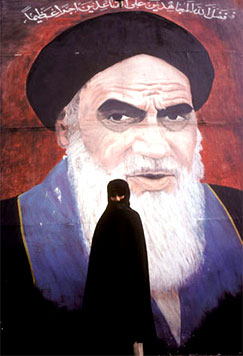

Meanwhile Ayatollah Khomeini had been issuing written and spoken statements and, to the desire of most people, insisting on the overthrow of the regime. In the face of official censorship, widespread use of photocopying facilities and cassette tapes played a crucial role in disseminating political news, statements and propaganda throughout the revolution.

The government being acutely aware of the uncompromising role played by Khomeini in Iraq in the absence of political restraint, brought pressure on the Iraqi government to restrict his activities. The ayatollah decided to move to Kuwait but the Kuwait government refused him leave of entry. It was at this point on 6 October that he responded to the call of a group of his supporters in France, to take the unlikely decision to fly to Paris. As things turned out, this decision played a major role in boosting revolutionary morale and turning the ayatollah into the undisputed leader and charismatic mentor of the revolution.

Once in Paris, he became the focus of attention of Western press and media, and the object of pilgrimage for thousands of Iranians in Europe, America and Iran itself. He was given the title of Imam, an extraordinary and therefore highly honorific one for a Shia leader outside the twelve sinless Imams. Not long afterwards, the rumour spread that Khomeini’s image could be seen on the moon, and it was believed by most Iranians, including some of the educated and modern, many of whom would testify to have seen it themselves.

On 5 November the people of Tehran ran riot, attacked public buildings and set fire to banks, liquor shops and cinemas, the army having stood aside apparently in order to show the gravity of the situation. A BBC television reporter was puzzled when he pointed to a man in an expensive suit and Pierre Cardin tie dancing around a burning tire and shouting revolutionary slogans.

The shah then appointed a military government headed by the dovish General Azhari, chief of the general staff, although many members of his cabinet were civilian. Large numbers of both secular and religious people began to shout the religious slogan Allaho Akbar (God is the Greatest) from their rooftops every night. Azhari said in a press conference that the slogans had come out of cassette tapes and had not been shouted by the people. Next day the people were shouting in a massive demonstration: Miserable Azhari! / Four-star donkey! / Keep saying it’s tapes / But tapes have no legs. On 6 November, the day Azhari took office, there took place one of the most remarkable events in the Iranian revolution: the shah’s television broadcast to the ‘dear people of Iran’ in a most humble manner, acknowledging their revolution, promising full and fundamental reform, the removal of injustice and corruption, and free elections and democratic government; and begging them to restore peace and order to make it possible to proceed with these reforms.

Ten percent of such a move six months before - even if not so blatantly spelled out - followed by action, would have gone a long way to defuse the situation. But now it was seen as a sign of weakness, an act of duplicity to deceive the public and buy time for a come-back. The political leaders and activists outside of the Islamist and Marxist-Leninist forces, who hoped, if not for dialogue and compromise, at least for the orderly transfer of power, were increasingly pushed into the margin by the force of popular anger and indignation: the most popular slogan was ‘Let him [the shah] go, and let there be flood afterwards’.

All this while America and Britain, the two most influential Western powers in Iran had been watching the events with growing concern, especially since the start and spread of the strikes. The shah did not trust Britain and believed that it was working against him. He pointed to the faithful reporting of the events by the BBC Persian service as evidence, but given his deeply ingrained general distrust of Britain he is unlikely to have thought otherwise in any case. And although he saw and sought the advice of the British ambassador regularly, he later showed in his memoirs that he did not trust the ambassador, despite the fact that each time the ambassador had emphasized that he was expressing his own personal opinion.

But by far the most significant Western power was the United States which the shah regarded as his most important foreign friend and mentor, and on which he was psychologically dependent. Although the Carter administration would not give blanket public support to the shah on matters regarding human rights and the sale of American arms, no-one in that administration wished the shah’s downfall. But the shah wanted more from America than good will and the expression of public and private support which he regularly received from them. He wanted a firm, clear and unambiguous directive on what he should do. He might have employed the ‘iron fist’ policy – their euphemism for a massively repressive military reprisal - had he been told by America that that was what they wanted him to do. The American ambassador explained to him that while he as the shah of Iran was free to take any decision he deemed necessary, America was not prepared to take responsibility for it. But American opinion was divided and, in particular, Zbigniew Brzezinski, the President’s National Security Adviser was prepared to go further than that, while Secretary of State Cyrus Vance tended more towards the ambassador’s view, and the president tried to steer a middle course.

The final act of the great drama was played by Shapur Bakhtiar (Bakhtiyar), deputy leader of the National Front, who accepted the shah’s invitation to form a cabinet. Bakhtiar had been a leading member of the Iran party and deputy minister of labour in Mosaddeq’s last cabinet, and had been briefly jailed a couple of times after the 1953 coup. The shah agreed to go on a trip abroad, and Bakhtiar presented his cabinet on 6 January 1979. Still staying near Paris, Khomeini declared Bakhtiar’s government illegal and advised the strikers other than the journalists not to return to work.

Bakhtiar’s government was totally rejected by all of the opposition parties as well as the general public, and not least by his own National Front who expelled him from their ranks and leadership, partly on the argument that he had not had their approval for accepting office. Thus, despite his hopes of bringing some of the revolutionary forces to his side, the only force he could depend on was the army, and as events were to prove, the army could not act independently when its only effective head had left the country. Before leaving, the shah had set up a royal council to oversee the Crown’s duties in his absence, but shortly after his departure from Iran the council’s chair flew to Paris and tendered his resignation to Khomeini.

The shah accompanied by Queen Farah left the country on 16 January, which proved to be a journey without return. Ten days later, Khomeini returned to Tehran to a tumultuous welcome. By that time, not only judges and high civil servants but even some ex-ministers, royal court officials and others related to the royal family had begun to support the revolution, and the only force still maintaining the regime was the army. But the army itself was not a uniform and homogeneous entity. The general staff were divided between a majority of ‘doves’ and a minority of ‘hawks’. Facing the soldiers in the streets, the people were shouting ‘Army brother, why kill your brother’, and putting flowers into the barrel of their guns. There was real fear of insubordination in the army ranks, especially given the religious aspects of the revolution. The lower ranks of the air force were publicly supporting the revolution with a number of them appearing in the massive street demonstrations in full uniform.

The units still zealously committed to the shah were the elite Imperial and Immortal Guards. On 5 February, a troop of the guards decided to teach a lesson to air force personnel - who were watching the video recording of Ayatollah Khomeini’s return to Iran, the live coverage of which had been stopped by the government - and attacked their barracks in Tehran. The airmen put up position and began to fight, while at the same time appealing to people for help. Large numbers of people led by young guerrillas went to their help and attacked the guards from the rear. Quickly, the situation got out of the control of both the revolutionary leaders and the government. Fearing civil war, on 11 February the army declared neutrality and withdrew to their barracks. The government thus collapsed and Bakhtiar went into hiding, only to appear in Paris sometime later. But, despite appeals by the provisional government for calm, the people went on to attack the main prisons and military barracks, almost all of which surrendered without a fight.

It was now the turn of the revolutionaries to turn on each other, which resulted in the complete triumph of the Islamic revolution.

The revolution that ‘should not have happened’

In some of its basic characteristics, the Iranian revolution did not conform to the usual norms of Western revolutions and especially the French and Russian revolutions with which it had been compared in the West while it was taking place. This became a puzzle, resulting in disappointment and disillusionment among western commentators within the first couple of years of the revolution’s triumph. For them, as much as for a growing number of modern Iranians who themselves had swelled the street crowds shouting ‘My dear Khomeini / Tell me to spill blood’, the revolution became ‘enigmatic’, ‘bizarre’, ‘unthinkable’. In the words of one western scholar, the revolution was ‘deviant’ because it established an Islamic republic and deviant also since ‘according to social-scientific explanations for revolution, it should not have happened at all, or when it did’. That is why large numbers of disillusioned Iranians began to add their voice to the shah and the small remnants of his regime in putting forward conspiracy theories, chiefly and plainly that America (and / or Britain) had been behind the revolution in order to stop the shah pushing for higher oil prices. Incredible as it may sound, it was even suggested that the West had been afraid that economic development under the shah would soon rob it of its markets.

Before the triumph of the revolution, this puzzle was somewhat closed to the eyes of Western liberals and leftists who at the time had a large amount of influence in Western governments, societies and media. But even Western conservatives did not suspect the revolution to turn out how it did after its triumph. All the signs had been there but they were largely glossed over by the massive peaceful processions, the solidarity and virtual unanimity of the society to overthrow the state, the blood sacrifice, and the phenomenon of Ayatollah Khomeini, pictured sitting under an apple tree near Paris with a smile on his face, every one of whose words were received as divine inspiration by the great majority of Iranians – modern as well as traditional - and who was the object of pilgrimage under the watchful eyes of Western media, which made him a permanent feature on television screens the world over. At the time, the revolution was seen as a massive revolt for freedom, independence, democracy or social justice - depending on the inclinations of the observer - and against oppression, corruption, social inequality and foreign domination. The anti-Western overtones of the movement were merely put down to ‘anti-imperialism’ and ‘nationalism’ (the words being applied almost interchangeably), and justified against the background of the 1953 coup, unsuspecting that some of the domestic Iranian forces involved in that coup were prominently represented in the revolution. The widespread and deeply felt anger against the West and all things western by the great majority of Iranians - both traditional and modern, both lay and intellectual - was thus viewed lightly as no more than a manifestation of such a nationalism and anti-imperialism.

Certainly the revolution could not be fully explained ‘according to social-scientific explanations for revolution’ for the simple reason that such explanations are based on the characteristics of Western revolutions, which themselves have in their background Western society, history and traditions. It is possible to make sense of Iranian revolutions by the application of the tools and methods of the same social sciences which have been used in explaining Western revolutions, but explanations which are based on Western history inevitably result in confusion and contradiction. The most obvious point of contrast is that in Western revolutions, the society was divided, and it was the underprivileged classes that revolted against the privileged classes who were most represented by the state. Whereas in Iranian revolutions it was the whole society which revolted against the state, there being no social class and no political organization standing against it, the state being defended by its coercive apparatus and nothing else. It was stark evidence against Euro-centric universalist theories of history. As Karl Popper once observed, there is no such thing as History; there are histories.

From Western perspectives, it would certainly make no sense for some of the richest classes of the society to finance and organize the movement, while a few of the others were sitting on the fence. Similarly, it would make no sense by Western criteria for the entire state apparatus (except the military who quit in the end) to go on an indefinite general strike, providing the most potent weapon for the success of the revolution. Nor would it make sense for almost the entire intellectual community and modern educated groups to rally behind Khomeini and his call for Islamic government. This was not a bourgeois capitalist revolution; it was not a liberal-democratic revolution; it was not a socialist revolution. Various ideologies were represented, of which the most dominant were the Islamic tendencies –Islamist, Marxist-Islamic and democratic-Islamic, on the one hand, and Marxist-Leninist tendencies: Fada’i, Tudeh, Maoist, Trotskyist, etc., on the other.

The conflict within the Islamic tendencies and the Marxist-Leninist tendencies themselves was probably no less intense than that between the two tendencies taken as a whole. Yet they were all united in the overriding objective of bringing down the shah and overthrowing the state. More effectively, the mass of the population who were not strictly ideological according to any of these tendencies – and of whom the modern middle classes were qualitatively the most important – were solidly behind the single objective of removing the shah. Any suggestion of a compromise would be dismissed as treason. And moreover, if any settlement had been reached, however peaceful and democratic, short of the overthrow of the monarchy, legends would have grown as to how the ‘liberal bourgeoisie’ had stabbed the revolution in the back on the order of their ‘foreign (i.e. American and British) masters’.

Gholamhosein Saedi - leading intellectual, writer and playwright as well as psychiatrist - who participated in the revolution but later fell out with the Islamic regime and died prematurely in his Paris exile in 1985 - wrote in Paris in 1984:

The whirlwind which…in 1977-1979 blew and whirled throughout Iran and overturned everything in its wake was at first the great revolt of all the masses, the solid and united action against a regime that had been insulting them for years. In those days if a stranger roamed around the city and just looked at the walls, he would know what was going on. The walls of all towns and cities were covered with writings which had only one motivation and one objective, and that was the overthrow of the royal regime.

True to the pattern of Iranian revolts, both traditional and modern, it was not just a revolution of the underprivileged against the ruling classes as had been virtually always the case in European revolutions, but the revolt of the whole society (mellat) against the state (dawlat) which was symbolized by and crystallized in one man alone. What bound them all together was the determination to remove that one man at all costs. As noted, the most widespread slogan which united the various revolutionary parties and their supporters regardless of party and programme was 'Let him [the shah] go and let there be flood afterwards' (In beravad va har cheh mikhahad beshavad). Many changed their minds in the following years but nothing was likely to make them see things differently at the time. Thirty years later, Ebrahim Yazdi, a leading aide of Ayatollah Khomeini in Paris and later foreign minister in the provisional government after the revolution was reported as speaking in Washington, ‘candidly of how his revolutionary generation had failed to see past the short-term goal of removing the shah...’

Those who lost their lives in various towns and cities throughout the revolution certainly played a major part in the process. But the outcome would have been significantly different if the commercial and financial classes, who had reaped such great benefits from the oil bonanza as few others had, had not financed the revolution, and - more especially - if the National Iranian Oil Company employees, high and low civil servants, judges, lawyers, university professors, intellectuals, journalists, school teachers, students, etc., had not joined in a general strike, or if the masses of the young and old, the modern and traditional, men and women, had not manned the huge street columns, or if the military had united and resolved to crush the movement.

The revolution of 1977-1979 and the Constitutional Revolution of 1906-1909 look poles apart in many respects. Yet they were quite similar with regard to some of their basic characteristics which may also help explain many of the divergences between them. Both of them were revolts of the society against the state, and as such cannot be easily explained with reference to Western traditions. Merchants, traders, intellectuals and urban masses played a vital role in the Constitutional Revolution. But so did leading ulama and powerful landlords, such that without their active support the triumph of 1909 would have been difficult to envisage, making it look as if ‘the church’ and ‘the feudal-aristocratic class’ were leading a ‘bourgeois democratic revolution’! In that revolution too various political movements and agendas were represented, but they were all united in the aim of overthrowing the arbitrary state (and ultimately Mohammad Ali Shah), which stood for traditionalism; so that, willy nilly, most of the religious forces also rallied behind the modernist cause. Walter Smart, the young British diplomat in Tehran wrote at the time that

in Persia religion has, by force of circumstances, perhaps, found itself on the side of Liberty, and it has not been found wanting. Seldom has a prouder or a stranger duty fallen to the lot of any Church than that of leading a democracy in the throes of revolution, so that [the religious leadership] threw the whole weight of its authority and learning on the side of liberty and progress, and made possible the regeneration of Persia in the way of constitutional Liberty.

It was equally puzzling for the BBC correspondent to watch a man in an expensive suit and Pierre Cardin tie in November 1978 in Tehran, dancing around a burning tire and shouting anti-shah and pro-Khomeini slogans. Many of the traditional forces backing the Constitutional Revolution regretted it after the event, as did many of the moderns who participated in the revolution of February 1979, when the outcomes of those revolutions ran contrary to their own best hopes and wishes. But no argument would have made them change their minds before the collapse of the respective regimes. There were those in both revolutions who saw that total revolutionary triumph would make some, perhaps many, of the revolutionaries regret the results afterwards, but very few of them dared to step forward. In the one case they were represented by Sheikh Fazlollah; in the other by Shahpur Bakhtiar. However, they were both doomed because they had no social base, or in other words they were seen as having joined the side of the state, however hard they protested that they had the best of intentions. It is a rule in a revolt against an arbitrary state that whoever wants anything short of its removal is branded a traitor. That is the logic of the slogan ‘Let him go and let there be flood afterwards!’

The Iranian revolution did not stop after February 1979, any more than the French revolution had stopped after July 1789 or August 1792, or the Russian revolution had concluded in February or October 1917. Even the Chinese revolution turned on its own children with delayed action in the 1960s and 70s. The single unifying aim of overthrowing the shah and the state having been achieved, it was now time for each party to try, not to share but grab as much as possible the spoils of the revolution. Apart from the virtually powerless liberal groups, headed by Mehdi Bazargan’s provisional government, most of the players were highly suspicious of one another’s motives, hoping to try and eliminate their rivals as best they could from the realm of political power. Apart from the liberals no one was interested in sazesh (compromise) the dirty word of Iranian politics.

There were two stages in the completion of the specifically Islamic revolution. The first was the occupation of the American embassy and taking American diplomats hostage in November 1979. The second stage was the impeachment and dismissal in June 1981 of Abolhasan Bani Sadr, the Islamic republic’s first president. But first and foremost in the minds of Ayatollah Khomeini and his lieutenants was the formal declaration of an Islamic republic. In a referendum held on 31 March the overwhelming majority of Iranians – both men and women, both modern and traditional, both rich and poor - voted for the creation of an Islamic republic; the official figure of 98.2 percent was probably close to reality. There were a few dissenting voices, because the nature of the republic had not yet been defined, and the only alternative offered to voters was the monarchy which they had so actively rejected. Bazargan was much criticized by the Islamists when at the polls he emphasized that he was voting for a democratic Islamic republic.

Bazargan had to resign in November 1979 upon the hostage taking of American diplomats by revolutionary zealots backed by Khomeini. In June 1981 the relatively moderate Abolhasan Banisadr was impeached and thrown out of the presidential office. Meanwhile Iraq had attacked Iran resulting in a long war which ended only in August 1988. There followed three presidencies, the first one (1989-1997) led by a pragmatist-conservative alliance, the second one (1997-1985), led by a reformist-pragmatist alliance, and the third one since 1985 led by a fundamentalist-conservative alliance, which increasingly tended to be more fundamentalist and less conservative. What the forthcoming presidential election of May 2009 will have in store for Iran no-one can predict with any degree of accuracy in that most unpredictable of modern societies.

Currently based at the University of Oxford, Homa Katouzian is a member of the Faculty of Oriental Studies and the Iran Heritage Research Fellow at St. Antony's College, where he edits the quarterly journal Iranian Studies. He is also a member of the Editorial Board of the Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

| Recently by Homa Katouzian | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Private Parts | 3 | Nov 04, 2009 |

| Beyond the Old and the New | 4 | Sep 04, 2009 |

| Wither Iran? | 28 | Aug 12, 2009 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

Iranian Revolution

by Pete Hudson (not verified) on Fri Jun 19, 2009 10:47 AM PDTIslamofascist Barack Obamai should be making announcements that support and encourage the Iranian revolution. I truly believe he hopes for the revolution's failure. Who cares if we're accused of meddling in Iranian affairs. Does the opinion or comments of that dictatorship matter?

Ahmadinejad is nothing more than a puppet of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei - Khamenei's front man. The real target is Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. A ruse election was held to create the illusion of democracy. Iran's dictatorship must be overthrown, and all of the top leadership (clergy, civilian and military) put to death. Then Iran can become free and democratic.

It will serve no purpose to have a reelection. Whoever is president, he/she will still be a stooge that serves as the mouthpiece of Khamenei.

To overthrow the dictatorship, a lot of blood will be shed, but that's necessary.

As the revolution continues the dictatorship will gradually fracture, and more and more of the military and police will join the revolt.

The revolution's success will be democracy's biggest plus in many years. Think about what it would do for Hezbollah, Hamas and world terrorism, and the blessing for Israel.

Democracies should be working on providing arms to the revolutionaries.

Pete Hudson

Ari

by Aristotle (not verified) on Sun Mar 15, 2009 03:48 AM PDTYou are more than welcome. Case Closed :-)

Aristotle

by Ari Siletz on Sat Mar 14, 2009 12:35 PM PDTAri, Adherents of cospiracy

by Ary, 'Politics Makes Strange Bed Fellows!' (not verified) on Fri Mar 13, 2009 11:46 AM PDTAri,

Adherents of cospiracy theory cannot only be found among the Islamists. To be sure, IRI's dominant tendency relies on anti-western stand for its legitimacy. And you are right; because of this, Katouzian's theory does not sit well with conservative forces within the present establishment.

But Leninists, Royalists and Nationalists have all been affected by views similar to Jaleho.

Leninists of all sorts have also habitually used the anti-imperialist stand as a cover for conspiracy theory -- every violation and criticism has been seen in this schema of things as reflection of British or U.S. imperialism (or up until the fall of USSR the Russian social imperialism).

So is the case with royalists. Mohammadreza Shah,for instance, believed almost all acts that were not in accordance with his wishes, were the result of this or that plot of 'red and black colonialism'; and in his book 'An Answer To History', he categorized Ebrahim Yazdi, Sadegh Ghotbzadeh -- and possibly Abolhassan Banisadr -- as CIA agents.

Nationalists have also toyed with this to explain (away) 1921 coup, Iranian railway as well as many other events. For years this view was blocking the pro-Mosaddegh activists from finding what was wrong with their strategy and tactics.

This seems to be changing. Among all political orientations, revisionists have poped up. Among royalists Daryoush Homayoun, among the old Tudeh activists Babak Amir-Khosravi and among Nationalist-Democrats Davoud Hermidas Bavand and their likes hold to this revisionist outlook that first and foremost identifies internal contelation of forces and realities as the primary cause for political events.

IRI has not been immune to this revisionism. Pro-reform elements such as Emadeddin Baghi, Abbas Abdi, Hashem Aghajari, Akbar Ganji, and many others are adherents of this revisionist view.

Even Mohammad Khatami and Mahdi Karubi stayed away from cospiracy theory as much as they could if you read between the lines; but they still have some catching up to do. The Islamic reformists' shortfalls in this area is not due to lack of knowledge. It is due pragmatic calculations that has to do with the risk of breaking the taboos of IRI and causiung the anger of Kayhan, Ahmadinejad and the principalists.

Jaleho's views on Iranian history, therefore, do not resonate with that of the reformed leftists, reformed royalists, reformed national-democrats and reformed Islamists. His views are in line with those of all orthodox elements of political spectrum from right to left, secular as well as religious.

Aristotle

Aristotle

by Ari Siletz on Thu Mar 12, 2009 04:15 PM PDT2. Absorbed the phenomenon of native collaborators into the theory.

3. Cited a piece of historical data that complicates Jaleho's Tobacco protest argument.

On a related matter, I am curious as to the policy consequences of this academic debate. For example, Iran's current government may be more inclined towards Jaleho's point of view because the IRI relies strongly on its anti-Western stance for its legitimacy. On the other hand, Katouzian's view might be perceived as a threat by the IRI because it can be used to posit a still unresolved dialectic between state and society. Are there policy motives to this debate?

Ari,Making good on my promise!

by Aristotle (not verified) on Thu Mar 12, 2009 10:50 AM PDTAri, Sorry for the delay.

Here are a few preliminary arguments that I believe refutes Jaleho's thesis about Katouzian's sins.

Jaleho claims that Katouzian 'stretches the "entire mellat vs. dowlat" in Iran's revolution too much to carry his point.'

My quesion is if Katouzian's stress on "entire mellat Vs. dolat" is too much then what is the right amount of stress? (Reminds me of Salieri criticizing Mozart saying 'too many notes!')

Jaleho uses a similar argument when he says "opposition to the state has not been as uniform as Katouzian indicates." my question again is how uniform is uniform? Does Jaleho have a yardstick?

Accoding to Jaleho, "in reality, there has been strata of nobility and native collaborators with the foreign colonialist in Iranian case". I fail to see how having native collaborators with foreign colonialists negates the conflict between the state and the people? Collaboration of disgruntled landlords against the state is nothing new either; nor has its history started with western colonialism. One can date back such collborations to the one with Arab conquerers.

Jaleho wants us to believe, 'people of various classes that participated in Iranian revolutions got their cohesion from that anti-colonial element of the struggle, not from the anti-estebdad class struggle like the western revolutions. That's why you have the Ulama, bazaaris, intelligentsia, workers and compador all participating in Iranian revolutions, beccasue of its "anti-essteemar" character, not the "anti-estebdad" side of the coin which is more represented by different class interests.'

But many of the ulama, bazaaris, intellegensia and workers that Jaleho points to would stage their sit-ins on British consulate -- hardly an evidence of anti-colonialism.

Jaleho has ended his statement by saying,'I know that I am writing foggy, but I hope that I were able to clarify my point a bit'. I think the firs part of this statement is quite correct. The second part is not.

Aristotle

Ari, You answered your own question!

by Aristotle (not verified) on Fri Feb 27, 2009 12:00 PM PSTDear Ari,

Thanks for your hospitality; makes me feel I am not writing on thin air :-)

Your especulation is right.

Katouzian's focus on Reza Khan is only tangential. That specific study was inspired in late 1990's by declassification of British secret documents having to do with that era. And like a good historian he read them all in a very short span of time and synthesized it with over thirty years of research on the issue in an article.

The background is interesting though.

An allusion to the issue first appeared in an article published in IJMES in 1978 and then again in an expanded form in his 1980 book 'The Political Economy Of Modern Iran 1926-1929'. In both he made it clear, even then, that he sees no evidence that Brits made Reza Khan Reza Shah.

Saying this in 1980 -- a year after the 1979 revolution -- would not make any one popular with the Iranian moral majority of Islamic, Leninist or National-Democratic variants. But Katouzian said it at the time because he wished to correct the collective prejudice by becoming the leading Iranian scholar who has publicly posed against conspiracy theory with an alternative systematic explanation.

As such, in that book, and later in his other books, he attempted to unveil the frugality of quick 'feel good let's be angry and do nothing or shoot ourseleves in the feet unfounded Uncle Napleonian' explanations for major historical events. This would pave the way for attracting attention to the root causes of such events.

When Katouzian saw a bird which looked like canary and sounded like a canary he would call it a canary. But when some thing walked like a duck and talked like a duck, for Katouzian, it was of course still a duck. Hence, the differential historical treatment of the coup that brought Reza Shah to power and the coup that brought Mohammad Reza Shah back from Italy.

The later studies of Mark Gasiorowski on the 1953 coup proved Katouzian right and added more details. The evidence was clear: the coup was inspired, planned and monitored by the foreingers; but was executed by the authoritarian forces and their temporary allies. And, as it happens in Iranian history it all played into the hands of despotic restoration.

TGIF,

Aristotle

Aristotle

by Ari Siletz on Thu Feb 26, 2009 12:52 PM PSTMeanwhile, as a Katouzian reader, I am curious as to why after he has produced such a consistent formula he labors over variables that neatly cancel in his arithmeitic anyway. In the example of Reza Khan, he fits very well in the Katouzianian cycle of despot, fetneh/ashoub, despot. It does not seem necessary to the theory to labor over whether Reza Khan was propped up by the British or not. Past Iranian despots may have been propped up by their local historical causes, but overall the only long-term pattern that survives is the cycle proposed by Katouzian. Or perhaps Katouzian's study of Reza Khan vis-a-vis British is an independent pursuit outside the logical chain of the theory; the reader muddying the discourse by incorrectly mixing the two.

As an unrelated thought, I favor Katouzian's approach becasue it emancipates Iranians from the paralysis of belief in political causes beyond their control. On the other hand the very power of this theory makes it worthy of debate, because if the Western hand is a bigger threat than the theory calculates then we need to correct the theory.

Ari and Parisa86

by Jaleho on Thu Feb 26, 2009 12:00 PM PSTAri, While I appreciate the good research and input of many intellectual Iranians, I also think that ignoring some well established essential facts, and rehashing it into "new" forms, is at best an over-wrought intellectual masturbation, and just good to pay the salary of certain historical and political chairs! Since I am an unknown nobody, I can sacrifice finesse for the sake of clarity as I believe an honest historical analysis is urgent to understand present events and a guide to avoid future mistakes.

I believe that the lack of clarity is not benign either. Being "ashamed" of the non-western religious massive current of Iranian population, denying the century long designs on Iran as a chess board of colonial powers, delusions of grandeur based on thousand years ago empire while ironically assuming that the same grand people can be manipulated like an ignorant herd of sheep ....has led to oversimplified pedestrian interpretations like "mullah are stupid and Islam bad," or "the good revolution was hijacked by bad religious people who came out of nowhere," or "revolution was staged by foreigners and Iranians just followed like sheep," or repeating Kinzer's story lines of " we at the west defeated the seculars, that gave rise to religious hegemony even the 9/11".....

That's why I believe that you can not underestimate the colonial base of Iranian revolutions, and you can not look at 1978-79 revolution without going back to the beginning of the Iranian awakening in Constitutional Revolution era. Also, the very good point of Parisa86 in her first paragraph regarding the "nation state" is well taken, but I think the comparison of Iranian revolutions with French revolution is overdone to a meaningless academic exercise. Revolutionary masses, do not go and read history of French revolution etc before pouring out in the streets. They are affected by overall historical and local events that shape their own uprising. Thus for more apt understanding of Iran's Constitutional Revolution and its varied participants we need to remember the more direct events that shaped it:

1. The Tobacco concession to Brits which led to Tobacco rebellion of 1891, an event that sealed the collaboration of clergy and bazaaris for the rest of the future anti-colonial struggles of Iran including the 1979 revolution,

2. The oil concession to D'arcy in 1901, another huge base of anti-colonial discontent was created,

3. The Russian Revolution of 1905 (itself affected by the French Revolution) which led to the establishment of State Duma in Russia, and establishment of Russian Constitution in 1906, yet it still kept the authority of the church and the supremacy of the Emperor, although it turned out to be the precursor of the 1917 revolution.

These internal and neighboring event in Iran led directly to Iran's Constitutional Revolution of 1905. While you can not deny the role of clergy in that revolution, you can not also deny that power of other religious leader against Ayatollah Nouri for example, and the power of "mashrooteh" over "mashrooeh." The "anti-estebdad va anti-esteemar" character in that revolution can not be made more clearly!

The 1978-79 revolution, although imbued with its own internal histories, like the failure of communist or nationalist struggles in Iran's more recent past, as in height of Tudeh power and National Front power, is still closely related to the constitutional revolution in its fundamentals. That is, you still had the same "anti-estebdad va anti-esteemar" sides of the coin, together with the participation of the same strata of people, including the clergy, bazzaris, intelligentsia and the leftists. It is not a paradox that Khomeini became the leader of the revolution whereas Ayatollah Nouri was executed in the Constitutional revolution at all! Many "mortaje" and anti-revolutionary clergy (to be compared with Nouri) were given the political pink slip during the 1979 revolution also!! Khomeini became the undeniable leader of the revolution not because of his religious status, but because of his uncompromising anti-colonial stance in his resume. He did not hijack the revolution, he was the strongest embodiment of the revolution, with the largest popular base.

Similarly, the Islamic rule was not artificially strengthened by the clergy extending the Iran-Iraq war. It was strengthened becasue the Iran-Iraq war was indeed a colonial war imposed on Iran, and once the Islamic leadership encapsulated that anti-colonial soul of Iranians leading it to defeat of colonial design to destroy the revolution, the revolution was consolidated further. You can not selectively forget that Saddam played in the hands of Americans, started his war by the old British tactics of claiming the Abu-Musa and Tunbs and Ahvaz as Arab land. Hence the anti-colonial Iranians wore the "Ya Hossein" badge on their head and went to war, unified by their religious leaders. They would have gone to defend the revolution with the same fervor had the righteous leaders of the revolutions were Martians instead of Ayatollahs!

You still observe the same anti-colonial and nationalism mixed and strengthening the Islamic leaders. Any wonder that the anti-Israel rhetoric of IRI leaders resonate so well with the anti-colonial Iranian populous? Any wonder that still an Ayatollah who blames Shah for giving Bahrain away to British demands, by calling it the "formerly 14 state of Iran" resonate so well with Iranian people?

Those who ignore the connection between the Iranian struggle against Tobacco concession of 1891 to Brits, oil concessions starting in 1901 and later given by Shah to Brits and Americans who kept him in power, and the Iranian insistence on their "inalienable right to nuclear energy," despite the heavy toll the western powers are imposing on them, will find the Islamic regime staying in power for 30 years a paradox, not a very natural thing.

PS. I'll wait for Aristotle and Plato to finish their critique of what I said to see if I have anything worthwhile to add :-)

No Dear Ari, Not at this price

by Aristotle (not verified) on Thu Feb 26, 2009 11:15 AM PSTDear Ari,

With all due respect, what you are suggesting here may make Jaleho happy, but it also will pull the sharpest tooth out of Homayoun Katouzian's theory.

The whole uniqueness and originality of Katouzian is in that since he was in his twenties, he rejected conspiracy theories. That is while royalists, left as well as almost all supporters of Dr Mosaddegh pointed to colonialism when they wished to explain -- or explain away -- every single major historical event. (I say almost all Dr Mosaddegh supporters because Katouzian at that time was himself an exception to the rule).

The pillar of Katouzian's explanation is that he makes us focus on the real causes of events and does justice to them according to their weight. In the healthy tradition of poiting to clouds as the more important cause of rain rather than the Gods, he encourages us to look at the historical inertia of the Iranian society -- i.e. despotism, which often divided Iranian society as you rightly mentioned between the state and the people.

Where Jaleho is mistaken is that if Katouzian goes against the dominant prejudice and popular wisdom and tells us that Reza Shah was not a lackey of the Brits or much less that the 1921 coup was not fabricated by them, it is because he finds no historical evidence that suggests it; and more importantly, finds plenty of eveidence that refutes the conjecture.

And where the evidence suggests a colonial or imperialistic inolvement -- the MI6-inspred and CIA-backed 1953 coup -- Katouzian enumerates the sequence of events, the historical context as well as the historical agents.

But even in 1951-1953, there was a real division between the state and the people the manifestation of which was the power struggle that resulted in the coup; the external forces of course used this dialectic in their own favor and added galons of fuel to the already existing fire. They did not start the fire. And this is only one example.

Even in this article which is the subject of discussion you see other examples of this. Jaleho can find them if he reads the article once more.

If my argument is convincing on this issue, then in my next posting, I will answer Jaleho's second unsound criticism regarding the level of influence and significance of private property and propertied classes in shaping political events.

My next posting will tackle Jaleho's charge that Katouzian overlooks the propertied classes.

Cheers,

Aristotle

I am not a royalist, but

by Tarikh (not verified) on Thu Feb 26, 2009 10:43 AM PSTI am not a royalist, but just wanted to bring to your attention the very same building attached to your post if indeed you have chosen it, is called Shahiad and built at the time of Mohmmad Reza.

To call the 1979 will of majority is too far fetched in my opinion. Were the chelo kabab khordeh Mellat aware of what was happening? I am not sure if it could be termed will of majority.

When all of us learn to remember history correctly, analyze it impartially and pass judgment without emotions and refrain from calling people names, then may be we are ready for the will of majority.

I 100% agree with you that Reza Pahlavi has no future in Iran, but if he holds a foreign passport is because IRS would not issue him and his family one.

Thanks for the link...

by Parisa86 (not verified) on Wed Feb 25, 2009 08:48 AM PSTI just want to reiterate though, in case it was unclear in my first post, that it is not my viewpoint that religion is the enemy of the state, simply that the two have deeply imbricated allegiances which are often misinterpreted, and to situate Islam as the Iranian people's opponent is a rather simple scapegoat mechanism that should be further examined. For example, to claim one's allegience to a purportedly secular state, is to forget the history of the emergence of "the state" to begin with. The nation-state is, in other words, a fairly recent global construct in light of Iran's long history and place in the Persian Empire. Moreover, it is a construct that might be said to be "foreign" to it, for it was not autonomously/culturally derived. By pledging allegience to the nation-state of Iran (which means excluding the surrounding regions which were once part of the Persian Empure and later reappropriated and charted into different nation-states) one is already pledging allegience to colonial constructs, if you will.

This latter reminds me of Abbas Milani's article on the three paradoxes of the Revolution (in the newsletter Aloha directed me to).

What I personally find to be the most interesting aspect of the Iranian Revolution is its similarity to the French Revolution in that, the latter took place coterminously with the evolution in thought that was occurring in European philosophy at the time--namely the Enlightenment. I don't know enough on the subject to speak as any kind of authority, but it seems to me that what the Iranians implicitly appropriated from Enlightenment thought was Kant's notion of subjectivity, which was, ironically enough, derived from Luther's theological examination of the divided subject. This seems to have been the direction al-Ahmad was going in when he was advocating for a notion of authentic Iranian subjectivity unadultrated by Western influence. Again, his oversight seems to have been ignoring the Judeo-Christian foundations latent in his own educational influence, which would have allowed him to arrive at such a viewpoint (for was he not "western" educated?).

That Iranians (religious clerics alike) henceforth believed it their prerogative to instigate a Revolution against the state in the first place, is evidence that they had adopted beliefs grounded in the European Englightenment, or at least those which had paved the way for the French Revolution--namely, that have-nots COULD have power, if only they made it their business to seize it.

What is ironic about all this of course, is that when Ayatollah Khomeini claimed power after the Shah was overthrown, he then decided that the Iranian people who had helped him attain power actually did not themselves warrant subjectivity, but subjecthood. They were subjects of God, not citizens of the state who could oppose regimes and instigate revolutions--in other words, they belonged to him (Khomeini) in a sense, needed to cultivate their religiosity, needed guidance, not the right to speak, but the didactic prescriptions of a "well-meaning" Islamic virtuoso like himself.

Obviously, power corrupts. Or, perhaps, as Nietzche observed, it is always metaphysical-minded people that turn power into violence. This does not, however, preclude the rash judgement that all of Islam is bad. Much less that religion as a whole is bad... we "secular"-minded people need to be careful about ourselves falling into the same metaphysical traps if we are not to become hypocrites.

Jaleho

by Ari Siletz on Tue Feb 24, 2009 11:55 PM PSTThanks Ari,

by Jaleho on Tue Feb 24, 2009 08:52 PM PSTI agree that there is no contradiction between anti-colonial struggle and the revolution against the state. In fact, Iranian revolutions starting with the Constitutional revolution have been clrealy and best characterized as "anti-estebdad va anti-esteemar."

My point is that Homayoun Katouzian decimates the "anti-esteemar" part of the Iranian revolutions (exemplified by his denial of the British role in 1921 coup), then incorrectly repackages it as a new theory of "mellat vs. dowlat" as the core distinction of Iran's revolution from the western revolutions, like French or Russian revolutions. Whereas, Iranian revolutions clearly had the "anti-estebdad" element in common with the French and Russian revolutions, but the latter naturally were not subject of western colonial designs! Whence lies their main distinction.

As such, I think Katouzian also stretches the "entire mellat vs. dowlat" in Iran's revolution too much to carry his point. In reality, there has been strata of nobility and native collaborators with the foreign colonialist in Iranian case, and oppositon to the state has not been as uniform as Katouzian indicates. People of various classes that participated in Iranian revolutions got their cohesion from that anti-colonial element of the struggle, not from the anti-estebdad class struggle like the western revolutions. That's why you have the Ulama, bazaaris, intelligentsia, workers and compador all participating in Iranian revolutions, beccasue of its "anti-essteemar" character, not the "anti-estebdad" side of the coin which is more represented by different class interests.

I know that I am writing foggy, but I hope that I were able to clarify my point a bit.

Let's start with the

by Aloha (not verified) on Tue Feb 24, 2009 02:55 PM PSTLet's start with the original colonialist:

You know the Islmaic/Arab colonization of Iran.

Though the Arab/Islamic armies at the gate have long gone but the perpetual inorganic Islamic colonialism of mind and soul keeps us as victims in perpetuity.

In a way, we never recovered from being defeated by Islam and we allowed ourselves to be victimized over and over and over and over again by variety of invaders.

Death to the Islamic colonialist/imperialist

jaleho

by Ari Siletz on Tue Feb 24, 2009 02:20 PM PSTKatouzian's study of the relationship between Iranian state and society begins with the Achaemenid legend of the imposter ruler Gautama before moving on to Alexander the great vs. Darius III. He continues with the rebellions against Sasanian arbitrary rule ending with the Arab invasion, and includes observations about the overthrow of the Ghaznavids by the Seljuqs and the overthrow of the Safavids by the Eastern Iranian Pashtuns. In each case certainly foreign interactions were the most obvious causes, but the underlying discontent leading to the upheaval can be viewed as internally fed by the anger of the entire population --mellat--against an arbitrary state--dowlat.

As an aside, according to Katouzian the mellat vs. dowlat dialectic of Iranian rebellions distinguishes itself from the Western variety where part of the society rises against another--not everybody vs. the state, as has been the pattern with Iran. Unlike their Western counterparts, Iranian aristocracy have never seen the dowlat as their representative.

A thousand years ago historian Baihaghi speaks of an aristocratic sycophant whom the Shah had praised as a "good donkey," to be held up as an example of loyalty. The aristocrat confides to the historian that he did not have the guts to tell the Shah that it is all of Khorasan's subjects, high and low, who suffer from the injustice.

How familiar does that sound?

to: Parisa86

by Aloha (not verified) on Tue Feb 24, 2009 11:56 AM PSTParisa86. I very much appreicate your insightful comment. The Iranian revolution in many ways resembles the French Revolution. It was a long overdue clash between the 'haves and the havenots'. The people's power was usurped by Islamists who subjuagted other Iranians will by sheer violence and brutality; very much like the French Jacobins. The Jacobins in Iran are still using the same tactics to stay in power. However, the revolution is entering another phase as did the French revolution; a Thermidorian phase as Dr. Akhavi aptly put it in his report.

I suggest you read the report by mideast.org. Though it's not by any means comprehesive enough but so far it's the best compilation of truths and half-truths since people tend to look for only one cause instead of mutliplicity of confounding factors. We need more original analysis and their collection for years to come to arrive at the big picture. The social psychology of the Iranians nation makes it so hard to pinpoint one cause or another.

In sum, There are multiple realties for realties are nothing but mere perceptions based on subjective biases.

The Truth is like a broken mirror and everyone holding a piece of that mirror belives he is holding the Truth; hence, the ongoing debate on etiology of the Iranian revolution.

Here is the report by mideast.org. You can find Mr. Katouzian's report in that document as well.

//www.mideasti.org/files/Iran_Final.pdf

The notion that militant

by shmaoniri (not verified) on Tue Feb 24, 2009 11:24 AM PSTThe notion that militant Islam a la Khomeini is anti-imperilist or anti-capitlaist or pro resistance is absurd and derenged on many levels.

Aversion to reality seems to reinforce the dogmatic, antiquated Islamic-Marxists. They distort the truth to fit into their little agenda at any price. It is sad to see such enslaved minds to ideology.

Anti-Colonial struggle was the heart of Iranian awakening

by Jaleho on Tue Feb 24, 2009 09:56 AM PSTThat's the core of Iranian struggle from the Constitutional Revolution of 1905 ignited in parts by the Oil concession given to D'arcy in 1901, and continued to 1921 coup, oil nationalization movement leading to the 1953 coup, 1960 revolts, and 1978-79 revolution. Ignoring this anti-colonial heart of Iranian awakening leads to non-analytical revision and interpretation of history in Iran in the last century. The same way that Homayoun Katouzian ignores the British role of Iran's 1921 coup, despite all the historical evidence, we are led to believe that the Islamic revolution is rooted in many things but that single most important factor of Iranian psyche: century long anti-colonial struggle with a similar composition of participants in all of these struggles; ulama and Tollab, bazaaris, intelligentsia and new comprador, and the urban workers and peasantry.

But, in this article we hear a lot of shoulda....woulda.... instead! If the oil price was not exploded in 1973-77...if Carter was not elected...If Shah has been more brutal in repression of the revolutionaries...if Shah had done the broadcast of reforms six months earlier even with 10% of the begging he did later....

We also read a lot of revision of history by those who don't like the Islamic form of the revolution, denying the actual role that religion and religious people have played in all of the Iranian anti-colonial struggle. Thus we see articles here claiming that National Front gave the power to the religious group in a silver platter, or Ayatollah Kashani was a British agent, and even Fadyan Islam were British tools, and the entire 1940-1950 struggle were conducted by either the communists (as in Tudeh) or intelligentsia, or Khomeini himself came to leadership because other groups failed and gave the religious faction power.... These arguments never refer to their own internal contradictions! For example, the violent Fadayan islam carried the terror of RazmAra and Mansour, people like Khalkhali which was its prominent head lasted well into the Islamic revolution... Or, if religious figures didn't have essential power in oil nationalization movement, why is that Ayatollah Kashani is referred to as keeping Mosaadeq in power as late as 1952, but his refusal to support Mossadeq any further in 1953 was the most significant element of the victory of 1953 coup? As a matter of fact, it seems that the Jebhe Melli leaders, from Bakhtyar to Bazargan were the people who were given the power in a silver platter, both by Shah and by Khomeini, and they failed to have the real popular base to lead!