به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

The Iranian Revolution at 30

by Homa Katouzian

22-Feb-2009

Lecture delivered at University of Amsterdam, 20 February 2009

Thirty years ago the Iranian revolution overthrew the Pahlavi monarchy in Iran. It subsequently became known as the Islamic revolution, although it had a much wider base than that, and it was only its further developments that led to the Islamic revolution.

The shah believed that he was highly popular with his own people, an illusion which was both due to the rapid increases in the standards of living and the fact that his system did not allow any criticism, least of all of his policies, to be made by anyone however high in society. He would therefore gauge his relationship with the people from sycophantic reports and stage-managed demonstrations of public support on certain occasions. His greatest tragedy, thus, was that he became a victim of his own propaganda.

The Politics of elimination

The politics of elimination had begun with the 1953 coup. Within two years after that coup, the communist Tudeh party and the democratic National Front had been eliminated from Iranian politics. The relatively gentle elimination of some of the loyal but independent-minded members of the regime later in the 1950s – for example, General Zahedi, Ali Amini and Abolhasan Ebtehaj– did not amount to a major change in the nature of the regime although it indicated the trend towards further concentration of power. This was also true of the increasing coolness of the relationship between the shah and the religious establishment from the mid-1950s. The power struggles of 1960-1963 could either result in a less dictatorial government within the existing system if Ali Amini or the second National Front had got the upper hand, or in absolute and arbitrary government, if the shah had managed to outwit them, as he in fact did. The shah then jettisoned any vestige of independent, though still very loyal, advice by men like Hossein Ala, Abdollah Entezam, Qa’em Maqam al-Molk, etc., etc., indeed the whole of the conservative establishment who had given him support through and after the 1953 coup, and who had ties with the religious establishment in Qom, Tehran, Mashahd and elsewhere. It was not so much the land reform alone that led to the great disenchantment of these groups, since its first stage, passed by Amini’s land reform law - though more genuine and less in the landlords’ favour than the second stage - had not led to an open confrontation by them. Much more provocative than land reform was the shah’s assumption of total power and the elimination of the political establishment from politics in the wake of his White Revolution.

The bazaar and the urban crowd had a far greater role than the land owning class in the revolt of June 1963, even though land reform did not threaten their interests at all. Even the students joined the demonstrations. Indeed in a published statement Ali Amini who was no friend of landlords condemned the way the revolt of June 1963 had been suppressed, and this led to a government order confining him to the city of Tehran.

The second National Front had not been an effective movement despite the widespread support that it had enjoyed at the time of its formation in 1960, largely as a result of the public good will towards Mohammad Mosaddeq. By 1964 it had completely run out of steam and was under heavy criticism from its own members such as the student movement and other Popular Movement organizations. The coup de grace was delivered by Mosaddeq himself who was drawn into the controversy by the critics and wrote highly critical letters about the Front’s ineptitude from his country residence to which he was forcibly confined by the government. The Front leaders resigned en masse and Mosaddeq gave the green light for the formation of the third National Front. This organization eventually came into being in 1965. Times however had changed and the shah would no longer tolerate so much as the existence of such moderate, open and peaceful organizations which could do little more than publishing critical leaflets and holding private meetings at their homes. From now on there had to be no dissenting voice of any kind.

The politics of elimination thus spelt doom for open, liberal and democratic movements, which, outside of the Tudeh party, had occupied the sphere of political opposition since Mosaddeq. In this way the field became wide open for guerrilla campaigns which began to take shape almost immediately after the onslaught against the democratic parties. Indeed the fiery and idealistic young people – mostly university students and graduates - who began to turn to violent solutions started by putting the blame for failure on democratic leaders themselves for choosing peaceful rather than violent tactics in their political struggles.

Society versus the State

The politics of elimination had a dialectical effect. While it led to the elimination of conservatives, liberals and democrats from politics, it encouraged the development of its opposites, namely beliefs, ideologies and movements which, one way or the other aimed at the overthrow of the regime and the elimination of the shah himself.

Many of the most secular intellectuals – virtually all leftists, and most of them Marxist-Leninists – began to discover the virtues of the county’s religious culture and traditions, decry Weststruckness, and advocate cultural authenticity and ‘nativism’. The terms gharbzadegi and gharbzadeh (variously translated, respectively, into Westoxication and Wetoxicated, Weststruckness and Weststruck, etc.) which the writer and intellectual Jalal Al-e Ahmad had used to attack the cultural and politico-economic influence of the West became everyday words used by members of virtually all classes to denounce state projects and decisions as well as anyone or anything they did not like.

The General Discontent

The revolution had many long and short causes, although it would not have turned into the revolt of the whole society against the state had the state enjoyed a reasonable amount of legitimacy and social base among some – at least the propertied and / or modern – social classes.

A major consequence of high, sustained and steady economic growth rates which were generated by increasing oil revenues was the rise of new classes in the society amid a high population growth rate. There thus developed a large community of traditional classes with good or reasonable standards of living and modern education, and a new sense of social confidence, which regarded the state as alien and oppressive. And large numbers of their young people adopted revolutionary attitudes, joining, supporting or at least applauding guerrilla activities and any other action against the regime. They believed, as did virtually all other opposition groups, that the regime was in the pockets of the West, and therefore extended their anger against it to western countries, especially America which was its strongest ally and had a considerable presence in the country.

However, the state’s biggest failure from the point of view of its own interest was that it alienated the modern social classes as well, at least some of which should have formed its social base. That would have been the case if the regime had been a dictatorship instead of a one-person arbitrary rule (estebdad), since it would have involved the participation of a political establishment in the running of the country, with the dual advantage of the regime benefiting from some critical discussion and advice, and the opposition not being blanket and comprehensive. Apart from that, the opposition would have faced not just one person, but a whole spectrum of ruling people who, when the chips were down, would have rallied round and defended the regime in their own interest.

Increasingly, not only traditional propertied classes, and not just the growing modern middle class professionals and middle income groups, but even modern propertied classes who owed much of their high fortunes to oil and the state were alienated from the regime. They did not have any independent economic and political power, and were critical of some of the economic policies of the state without there being a forum or channel for airing them. No criticism of the regime, however mild and well-intentioned, would in any case be tolerated, even if expressed in private. This was the greatest single grievance of intellectuals, writers, poets, journalists, etc., against the regime. Censorship was very strong, but, as noted, any verbal criticism, if reported, would also be duly punished.

The oil revenue explosion of 1973-1974 ironically had very negative consequences for the regime. It greatly enhanced its sense of self-confidence, and led to greater repression and a more arrogant attitude and behaviour towards the public. More than that, the economic consequences of the new oil bonanza and the political decisions to which they led resulted in widespread public indignation. The quadrupling of the oil prices almost immediately led to a massive increase in public expenditure, including the doubling of the expenditure estimates for the fifth economic plan. As both state and private incomes rose sharply so did consumption and investment expenditure, fuelling demand inflation. At the same time since the supply of many products ranging from fresh meat to cement could not be sharply increased from the domestic sources, supply shortages developed in the midst of financial plenty. Imports could not relieve the situation adequately partly because they would take time to deliver, partly because (as in the case of fresh local meat) imports were not possible, but mainly because of limits to port as well as storage and transport facilities, which could only be extended in the long run.

The general rise in prices had other consequences for spreading anger among important social classes such as traders, merchants and business people. While, as noted, excessive state spending was the principal cause of rising inflation, it blamed it on hoarding and profiteering on the part of producers, wholesalers and retailers. Prices of a number of commodities were reduced by fiat. A public campaign was launched against ‘profiteering’ (geranforushi), involving thousands of young men as agents of the official Rastakhiz party who were sent to the bazaars, shops and other business premises to find the culprits and take swift administrative measures against them. Hundreds of merchants and traders, including one or two leading businessmen, were arrested. Others were fined. Shops were closed down and trading licences were cancelled. This did little to relieve the inflationary pressures, but it spread and intensified anger among the business community, both traditional and modern. Nor did it satisfy the ordinary public who came to see merchants and businessmen as scapegoats for the state’s arbitrary policies.

Given the state and scale of discontent among the various classes and communities of the society briefly described above, it is not surprising that the revolution proved to be so widespread when it came. Still, the protest movement would not necessarily have resulted in a full-scale revolution, had the state responded to its earlier stages differently than it did.

The protest movement

It is always difficult to discover with certainly the origins of any revolution. The origin of the February 1979 revolution is sometimes put as far back as the coup d’etat of August 1953. But in fact many things might or might not have happened between 1953 and 1979 which could have avoided the revolution, the larger factors being the revolt of June 1963, the rise of the shah’s arbitrary rule, and the quadrupling of the oil prices in 1973-74 which further enhanced the arbitrary power of the state and led to misguided economic policies. Thus the long-term origins of the revolution may be said to go back to the 1960s when the upper and modern social classes were eliminated from politics; and the short-term factors stemmed from the explosion of oil revenues which led to the intensification of absolute and arbitrary rule, with the result that, as noted above, virtually the whole of

the society became alienated from the state.

Ironically, it was President Carter’s election in November 1976 and the Iranian regime’s quick response to it which helped to launch the protest movement. For a decade already, evidence of severe human rights violations had been slowly building up in the reports of such important Western human rights organizations as Amnesty International as well as the press and media.

Amnesty’s first major report on Iran which closely documented widespread legal violations and human rights abuses was published in the same month that Jimmy Carter was elected president. In February 1976, a detailed article on torture on Iran appeared in Index on Censorship, the reproduction of excerpts from which in New York Times had a significant impact on the wider political circles in America. A major foreign policy point of Carter’s campaign was his emphasis on human rights. The main targets were the Soviet Union and other socialist countries, but also some Latin American countries, e.g. Nicaragua, whose illiberal regimes had been traditionally backed by US administrations. However, Carter did not pass any public comments on the human rights situation in Iran, either then or later when he became president. The shah, on the other, hand, did not have good memories of Democratic presidents such as John Kennedy and generally regarded Democratic administrations as being critical of his regime.

The inauguration of President Kennedy in 1960 had prompted the shah to allow for a certain amount of liberalization which had been followed by the power struggles of 1960-1963, ending with his assumption of total power. His immediate response to Carter was similar. Early in 1977, he announced the end of torture in Iran, and by August of that year he had pardoned 357 political prisoners. And although censorship of the press was still very strong, it became possible to publish articles, for example, on the difficulties faced by Iranian agriculture.

All this was seen by the opposition as a sign of the shah’s weakness, almost literally believing that he had been ordered by Carter to relax his regime, though their analyses of the possible causes of this was varied and typically fanciful. They talked about ‘the change in the international atmosphere’, meaning the attitude of America towards the shah’s regime. Thus emboldened, on 13 June 1977 the Writers’ Association which had never had the right to function normally issued an open letter demanding basic rights. Signed by forty writers, poets and critics, it was addressed to Prime Minister Hoveyda and asked for official permission to open a public office for the Association. This was followed on 19 July by another open letter on the same theme, signed by ninety-nine authors. Shortly before this, a group of prominent advocates had signed a public statement demanding the return of judicial power and status to the law courts.

Within a couple of months a number of political and professional associations were reconstituted or came into being. Almost all of these organizations had liberal-democratic tendencies, asking for freedom of expression, the enforcement of the county’s constitution, the return of judicial processes, etc. They did include both leftist elements and Islamic views, but until after ‘the Poetry Nights’ of November 1977, the far left and the Islamist movement – which later set the goal of overthrowing the regime – were still in the background.

Feeling the pressure from without and within, in August the shah dismissed Prime Minister Hoveyda’s cabinet, making Hoveyda himself minister of the royal court. Meanwhile there had been a series of demonstrations and strikes at universities throughout the country, which was to increase in extent and frequency as the movement continued. The campaign for freedom and human rights, still short of a general call for the overthrow of the regime, peaked during the ten nights of poetry reading sessions, held in November, at the German cultural centre, the Goethe Institute, and Aryamehr technical university. Attended by thousands of people, they were organized by the Writers

Association and became known as The Poetry Nights, until the tenth night when they were broken up by the police.

Also in November, the shah paid a state visit to the United States, and while he was being welcomed by President Carter on the lawns of the White House, Iranian students demonstrating against him clashed with a small number of his well-wishers, and the police firing tear gas resulted in the shah, Carter and their suite to appear weeping live on television. Viewers also heard the slogan ‘Death to the shah’ for the first time, being shouted by the demonstrators outside the White House, before it became a regular slogan in the streets of Iranian cities less than a year later. The shah returned to a warm but officially organized welcome, and a few weeks later Carter celebrated the New Year as the shah’s guest in Tehran. Both in Washington and in Tehran, the president was fully supportive of the shah, emphasizing Iran-American friendship and cooperation.

Revolution

Until then the campaign had had more of the character of a protest or reform movement, although there certainly were revolutionary forces ready to come forward at the right moment. The first such opportunity was offered by the official vilification of Ayatollah Khomeini in the press. Earlier, the Ayatollah had issued a statement from his place of exile in Najaf ( Iraq) attacking the shah, calling the shah a servant of America, and saying that the Iranian people would not rest in their struggle against his regime. Signed under a pseudonym, the article against him was published on 7 January 1978 in the leading semi-official daily Ettela’at against the best judgement of its editor who feared a strong public reaction. It described Khomeini as an agent of both Black (i.e. British) and Red (i.e. Soviet) imperialism, ‘an adventurous cleric, subservient to centres of colonialism’.

The reaction in Qom was swift and angry. Copies of the newspaper in which the article had been published were torn and burnt. The religious colleges and bazaar were shut down. There were public clashes with the security forces, and an attack on 9 January on the headquarters of the official Rastakhiz (Resurgence) party led to civilian casualties, the official figure being two dead, the opposition figures, 70 dead and 500 injured.

On 19 February 1978, the ritual 40th day of the mourning for those killed in Qom, there were vast demonstrations in Tabriz, most of whose people were followers of the moderate Grand Ayatollah Shariatmadari, the senior marja’ in Qom. Once again, clashes with the security forces led to bloodshed and widely different figures for the dead and wounded were quoted by the government and the opposition. In turn, the 40th day of the dead of Tabriz resulted in demonstrations and bloodshed in various cities, and thus the 40-day cycle became a familiar event in the revolutionary process.

Qom, then, was the first major turning point. The second major turning point of the revolution occurred on 19 August 1978. The Cinema Rex in Abadan – Iran’s oil capital – was set ablaze by unknown arsonists resulting in the death of 400 and more people inside. The crime was never fully investigated either before or after the revolution and it is not known who or what the culprits were. But the state got the blame, partly as a matter of course, and partly because it had been putting out propaganda that the opposition were utter reactionaries, opposed to all things modern, including cinemas. The public then believed that this was done by the state to blame it on the opposition and prove their point.

The third major turning point came on 8 September, subsequently dubbed Black Friday. Four days before, the great Islamic festival of Fitr, concluding the month of fasting, had been celebrated by tens of thousands of people in a mass prayer held in the streets of Tehran, led by a revolutionary cleric. This was followed the next day by a demonstration of a crowd of more than a hundred thousand people who for the first time shouted ‘Say death to the shah’. A huge rally was called for Friday 8 September in Tehran’s Zhaleh Square (Friday being weekend in Iran) but the night before martial law was declared in Tehran and 12 other cities and all public meetings were banned. It is likely that, as it was said at the time, the public did not receive the news of the new measures in time. At any rate, an anticipated huge crowd gathered in Zhaleh Square at the appointed time and were told by the general administrator of martial law to disperse. When they refused, and after a round of warning shots in the air, the soldiers fired into the crowd.

There was a lull for a couple of days but street clashes often resulting in bloodshed were soon resumed, massive demonstrations (sometimes by one or two million people) were organized, and there were political strikes by industrial workers, oil company workers and employees, the press, National Bank and other government employees, eventually embracing virtually every profession. At one point judges and the whole of the department of justice also went on strike.

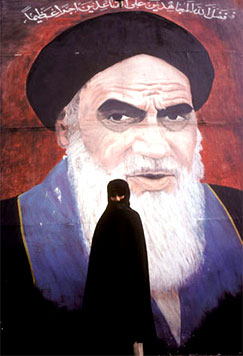

Meanwhile Ayatollah Khomeini had been issuing written and spoken statements and, to the desire of most people, insisting on the overthrow of the regime. In the face of official censorship, widespread use of photocopying facilities and cassette tapes played a crucial role in disseminating political news, statements and propaganda throughout the revolution.

The government being acutely aware of the uncompromising role played by Khomeini in Iraq in the absence of political restraint, brought pressure on the Iraqi government to restrict his activities. The ayatollah decided to move to Kuwait but the Kuwait government refused him leave of entry. It was at this point on 6 October that he responded to the call of a group of his supporters in France, to take the unlikely decision to fly to Paris. As things turned out, this decision played a major role in boosting revolutionary morale and turning the ayatollah into the undisputed leader and charismatic mentor of the revolution.

Once in Paris, he became the focus of attention of Western press and media, and the object of pilgrimage for thousands of Iranians in Europe, America and Iran itself. He was given the title of Imam, an extraordinary and therefore highly honorific one for a Shia leader outside the twelve sinless Imams. Not long afterwards, the rumour spread that Khomeini’s image could be seen on the moon, and it was believed by most Iranians, including some of the educated and modern, many of whom would testify to have seen it themselves.

On 5 November the people of Tehran ran riot, attacked public buildings and set fire to banks, liquor shops and cinemas, the army having stood aside apparently in order to show the gravity of the situation. A BBC television reporter was puzzled when he pointed to a man in an expensive suit and Pierre Cardin tie dancing around a burning tire and shouting revolutionary slogans.

The shah then appointed a military government headed by the dovish General Azhari, chief of the general staff, although many members of his cabinet were civilian. Large numbers of both secular and religious people began to shout the religious slogan Allaho Akbar (God is the Greatest) from their rooftops every night. Azhari said in a press conference that the slogans had come out of cassette tapes and had not been shouted by the people. Next day the people were shouting in a massive demonstration: Miserable Azhari! / Four-star donkey! / Keep saying it’s tapes / But tapes have no legs. On 6 November, the day Azhari took office, there took place one of the most remarkable events in the Iranian revolution: the shah’s television broadcast to the ‘dear people of Iran’ in a most humble manner, acknowledging their revolution, promising full and fundamental reform, the removal of injustice and corruption, and free elections and democratic government; and begging them to restore peace and order to make it possible to proceed with these reforms.

Ten percent of such a move six months before - even if not so blatantly spelled out - followed by action, would have gone a long way to defuse the situation. But now it was seen as a sign of weakness, an act of duplicity to deceive the public and buy time for a come-back. The political leaders and activists outside of the Islamist and Marxist-Leninist forces, who hoped, if not for dialogue and compromise, at least for the orderly transfer of power, were increasingly pushed into the margin by the force of popular anger and indignation: the most popular slogan was ‘Let him [the shah] go, and let there be flood afterwards’.

All this while America and Britain, the two most influential Western powers in Iran had been watching the events with growing concern, especially since the start and spread of the strikes. The shah did not trust Britain and believed that it was working against him. He pointed to the faithful reporting of the events by the BBC Persian service as evidence, but given his deeply ingrained general distrust of Britain he is unlikely to have thought otherwise in any case. And although he saw and sought the advice of the British ambassador regularly, he later showed in his memoirs that he did not trust the ambassador, despite the fact that each time the ambassador had emphasized that he was expressing his own personal opinion.

But by far the most significant Western power was the United States which the shah regarded as his most important foreign friend and mentor, and on which he was psychologically dependent. Although the Carter administration would not give blanket public support to the shah on matters regarding human rights and the sale of American arms, no-one in that administration wished the shah’s downfall. But the shah wanted more from America than good will and the expression of public and private support which he regularly received from them. He wanted a firm, clear and unambiguous directive on what he should do. He might have employed the ‘iron fist’ policy – their euphemism for a massively repressive military reprisal - had he been told by America that that was what they wanted him to do. The American ambassador explained to him that while he as the shah of Iran was free to take any decision he deemed necessary, America was not prepared to take responsibility for it. But American opinion was divided and, in particular, Zbigniew Brzezinski, the President’s National Security Adviser was prepared to go further than that, while Secretary of State Cyrus Vance tended more towards the ambassador’s view, and the president tried to steer a middle course.

The final act of the great drama was played by Shapur Bakhtiar (Bakhtiyar), deputy leader of the National Front, who accepted the shah’s invitation to form a cabinet. Bakhtiar had been a leading member of the Iran party and deputy minister of labour in Mosaddeq’s last cabinet, and had been briefly jailed a couple of times after the 1953 coup. The shah agreed to go on a trip abroad, and Bakhtiar presented his cabinet on 6 January 1979. Still staying near Paris, Khomeini declared Bakhtiar’s government illegal and advised the strikers other than the journalists not to return to work.

Bakhtiar’s government was totally rejected by all of the opposition parties as well as the general public, and not least by his own National Front who expelled him from their ranks and leadership, partly on the argument that he had not had their approval for accepting office. Thus, despite his hopes of bringing some of the revolutionary forces to his side, the only force he could depend on was the army, and as events were to prove, the army could not act independently when its only effective head had left the country. Before leaving, the shah had set up a royal council to oversee the Crown’s duties in his absence, but shortly after his departure from Iran the council’s chair flew to Paris and tendered his resignation to Khomeini.

The shah accompanied by Queen Farah left the country on 16 January, which proved to be a journey without return. Ten days later, Khomeini returned to Tehran to a tumultuous welcome. By that time, not only judges and high civil servants but even some ex-ministers, royal court officials and others related to the royal family had begun to support the revolution, and the only force still maintaining the regime was the army. But the army itself was not a uniform and homogeneous entity. The general staff were divided between a majority of ‘doves’ and a minority of ‘hawks’. Facing the soldiers in the streets, the people were shouting ‘Army brother, why kill your brother’, and putting flowers into the barrel of their guns. There was real fear of insubordination in the army ranks, especially given the religious aspects of the revolution. The lower ranks of the air force were publicly supporting the revolution with a number of them appearing in the massive street demonstrations in full uniform.

The units still zealously committed to the shah were the elite Imperial and Immortal Guards. On 5 February, a troop of the guards decided to teach a lesson to air force personnel - who were watching the video recording of Ayatollah Khomeini’s return to Iran, the live coverage of which had been stopped by the government - and attacked their barracks in Tehran. The airmen put up position and began to fight, while at the same time appealing to people for help. Large numbers of people led by young guerrillas went to their help and attacked the guards from the rear. Quickly, the situation got out of the control of both the revolutionary leaders and the government. Fearing civil war, on 11 February the army declared neutrality and withdrew to their barracks. The government thus collapsed and Bakhtiar went into hiding, only to appear in Paris sometime later. But, despite appeals by the provisional government for calm, the people went on to attack the main prisons and military barracks, almost all of which surrendered without a fight.

It was now the turn of the revolutionaries to turn on each other, which resulted in the complete triumph of the Islamic revolution.

The revolution that ‘should not have happened’

In some of its basic characteristics, the Iranian revolution did not conform to the usual norms of Western revolutions and especially the French and Russian revolutions with which it had been compared in the West while it was taking place. This became a puzzle, resulting in disappointment and disillusionment among western commentators within the first couple of years of the revolution’s triumph. For them, as much as for a growing number of modern Iranians who themselves had swelled the street crowds shouting ‘My dear Khomeini / Tell me to spill blood’, the revolution became ‘enigmatic’, ‘bizarre’, ‘unthinkable’. In the words of one western scholar, the revolution was ‘deviant’ because it established an Islamic republic and deviant also since ‘according to social-scientific explanations for revolution, it should not have happened at all, or when it did’. That is why large numbers of disillusioned Iranians began to add their voice to the shah and the small remnants of his regime in putting forward conspiracy theories, chiefly and plainly that America (and / or Britain) had been behind the revolution in order to stop the shah pushing for higher oil prices. Incredible as it may sound, it was even suggested that the West had been afraid that economic development under the shah would soon rob it of its markets.

Before the triumph of the revolution, this puzzle was somewhat closed to the eyes of Western liberals and leftists who at the time had a large amount of influence in Western governments, societies and media. But even Western conservatives did not suspect the revolution to turn out how it did after its triumph. All the signs had been there but they were largely glossed over by the massive peaceful processions, the solidarity and virtual unanimity of the society to overthrow the state, the blood sacrifice, and the phenomenon of Ayatollah Khomeini, pictured sitting under an apple tree near Paris with a smile on his face, every one of whose words were received as divine inspiration by the great majority of Iranians – modern as well as traditional - and who was the object of pilgrimage under the watchful eyes of Western media, which made him a permanent feature on television screens the world over. At the time, the revolution was seen as a massive revolt for freedom, independence, democracy or social justice - depending on the inclinations of the observer - and against oppression, corruption, social inequality and foreign domination. The anti-Western overtones of the movement were merely put down to ‘anti-imperialism’ and ‘nationalism’ (the words being applied almost interchangeably), and justified against the background of the 1953 coup, unsuspecting that some of the domestic Iranian forces involved in that coup were prominently represented in the revolution. The widespread and deeply felt anger against the West and all things western by the great majority of Iranians - both traditional and modern, both lay and intellectual - was thus viewed lightly as no more than a manifestation of such a nationalism and anti-imperialism.

Certainly the revolution could not be fully explained ‘according to social-scientific explanations for revolution’ for the simple reason that such explanations are based on the characteristics of Western revolutions, which themselves have in their background Western society, history and traditions. It is possible to make sense of Iranian revolutions by the application of the tools and methods of the same social sciences which have been used in explaining Western revolutions, but explanations which are based on Western history inevitably result in confusion and contradiction. The most obvious point of contrast is that in Western revolutions, the society was divided, and it was the underprivileged classes that revolted against the privileged classes who were most represented by the state. Whereas in Iranian revolutions it was the whole society which revolted against the state, there being no social class and no political organization standing against it, the state being defended by its coercive apparatus and nothing else. It was stark evidence against Euro-centric universalist theories of history. As Karl Popper once observed, there is no such thing as History; there are histories.

From Western perspectives, it would certainly make no sense for some of the richest classes of the society to finance and organize the movement, while a few of the others were sitting on the fence. Similarly, it would make no sense by Western criteria for the entire state apparatus (except the military who quit in the end) to go on an indefinite general strike, providing the most potent weapon for the success of the revolution. Nor would it make sense for almost the entire intellectual community and modern educated groups to rally behind Khomeini and his call for Islamic government. This was not a bourgeois capitalist revolution; it was not a liberal-democratic revolution; it was not a socialist revolution. Various ideologies were represented, of which the most dominant were the Islamic tendencies –Islamist, Marxist-Islamic and democratic-Islamic, on the one hand, and Marxist-Leninist tendencies: Fada’i, Tudeh, Maoist, Trotskyist, etc., on the other.

The conflict within the Islamic tendencies and the Marxist-Leninist tendencies themselves was probably no less intense than that between the two tendencies taken as a whole. Yet they were all united in the overriding objective of bringing down the shah and overthrowing the state. More effectively, the mass of the population who were not strictly ideological according to any of these tendencies – and of whom the modern middle classes were qualitatively the most important – were solidly behind the single objective of removing the shah. Any suggestion of a compromise would be dismissed as treason. And moreover, if any settlement had been reached, however peaceful and democratic, short of the overthrow of the monarchy, legends would have grown as to how the ‘liberal bourgeoisie’ had stabbed the revolution in the back on the order of their ‘foreign (i.e. American and British) masters’.

Gholamhosein Saedi - leading intellectual, writer and playwright as well as psychiatrist - who participated in the revolution but later fell out with the Islamic regime and died prematurely in his Paris exile in 1985 - wrote in Paris in 1984:

The whirlwind which…in 1977-1979 blew and whirled throughout Iran and overturned everything in its wake was at first the great revolt of all the masses, the solid and united action against a regime that had been insulting them for years. In those days if a stranger roamed around the city and just looked at the walls, he would know what was going on. The walls of all towns and cities were covered with writings which had only one motivation and one objective, and that was the overthrow of the royal regime.

True to the pattern of Iranian revolts, both traditional and modern, it was not just a revolution of the underprivileged against the ruling classes as had been virtually always the case in European revolutions, but the revolt of the whole society (mellat) against the state (dawlat) which was symbolized by and crystallized in one man alone. What bound them all together was the determination to remove that one man at all costs. As noted, the most widespread slogan which united the various revolutionary parties and their supporters regardless of party and programme was 'Let him [the shah] go and let there be flood afterwards' (In beravad va har cheh mikhahad beshavad). Many changed their minds in the following years but nothing was likely to make them see things differently at the time. Thirty years later, Ebrahim Yazdi, a leading aide of Ayatollah Khomeini in Paris and later foreign minister in the provisional government after the revolution was reported as speaking in Washington, ‘candidly of how his revolutionary generation had failed to see past the short-term goal of removing the shah...’

Those who lost their lives in various towns and cities throughout the revolution certainly played a major part in the process. But the outcome would have been significantly different if the commercial and financial classes, who had reaped such great benefits from the oil bonanza as few others had, had not financed the revolution, and - more especially - if the National Iranian Oil Company employees, high and low civil servants, judges, lawyers, university professors, intellectuals, journalists, school teachers, students, etc., had not joined in a general strike, or if the masses of the young and old, the modern and traditional, men and women, had not manned the huge street columns, or if the military had united and resolved to crush the movement.

The revolution of 1977-1979 and the Constitutional Revolution of 1906-1909 look poles apart in many respects. Yet they were quite similar with regard to some of their basic characteristics which may also help explain many of the divergences between them. Both of them were revolts of the society against the state, and as such cannot be easily explained with reference to Western traditions. Merchants, traders, intellectuals and urban masses played a vital role in the Constitutional Revolution. But so did leading ulama and powerful landlords, such that without their active support the triumph of 1909 would have been difficult to envisage, making it look as if ‘the church’ and ‘the feudal-aristocratic class’ were leading a ‘bourgeois democratic revolution’! In that revolution too various political movements and agendas were represented, but they were all united in the aim of overthrowing the arbitrary state (and ultimately Mohammad Ali Shah), which stood for traditionalism; so that, willy nilly, most of the religious forces also rallied behind the modernist cause. Walter Smart, the young British diplomat in Tehran wrote at the time that

in Persia religion has, by force of circumstances, perhaps, found itself on the side of Liberty, and it has not been found wanting. Seldom has a prouder or a stranger duty fallen to the lot of any Church than that of leading a democracy in the throes of revolution, so that [the religious leadership] threw the whole weight of its authority and learning on the side of liberty and progress, and made possible the regeneration of Persia in the way of constitutional Liberty.

It was equally puzzling for the BBC correspondent to watch a man in an expensive suit and Pierre Cardin tie in November 1978 in Tehran, dancing around a burning tire and shouting anti-shah and pro-Khomeini slogans. Many of the traditional forces backing the Constitutional Revolution regretted it after the event, as did many of the moderns who participated in the revolution of February 1979, when the outcomes of those revolutions ran contrary to their own best hopes and wishes. But no argument would have made them change their minds before the collapse of the respective regimes. There were those in both revolutions who saw that total revolutionary triumph would make some, perhaps many, of the revolutionaries regret the results afterwards, but very few of them dared to step forward. In the one case they were represented by Sheikh Fazlollah; in the other by Shahpur Bakhtiar. However, they were both doomed because they had no social base, or in other words they were seen as having joined the side of the state, however hard they protested that they had the best of intentions. It is a rule in a revolt against an arbitrary state that whoever wants anything short of its removal is branded a traitor. That is the logic of the slogan ‘Let him go and let there be flood afterwards!’

The Iranian revolution did not stop after February 1979, any more than the French revolution had stopped after July 1789 or August 1792, or the Russian revolution had concluded in February or October 1917. Even the Chinese revolution turned on its own children with delayed action in the 1960s and 70s. The single unifying aim of overthrowing the shah and the state having been achieved, it was now time for each party to try, not to share but grab as much as possible the spoils of the revolution. Apart from the virtually powerless liberal groups, headed by Mehdi Bazargan’s provisional government, most of the players were highly suspicious of one another’s motives, hoping to try and eliminate their rivals as best they could from the realm of political power. Apart from the liberals no one was interested in sazesh (compromise) the dirty word of Iranian politics.

There were two stages in the completion of the specifically Islamic revolution. The first was the occupation of the American embassy and taking American diplomats hostage in November 1979. The second stage was the impeachment and dismissal in June 1981 of Abolhasan Bani Sadr, the Islamic republic’s first president. But first and foremost in the minds of Ayatollah Khomeini and his lieutenants was the formal declaration of an Islamic republic. In a referendum held on 31 March the overwhelming majority of Iranians – both men and women, both modern and traditional, both rich and poor - voted for the creation of an Islamic republic; the official figure of 98.2 percent was probably close to reality. There were a few dissenting voices, because the nature of the republic had not yet been defined, and the only alternative offered to voters was the monarchy which they had so actively rejected. Bazargan was much criticized by the Islamists when at the polls he emphasized that he was voting for a democratic Islamic republic.

Bazargan had to resign in November 1979 upon the hostage taking of American diplomats by revolutionary zealots backed by Khomeini. In June 1981 the relatively moderate Abolhasan Banisadr was impeached and thrown out of the presidential office. Meanwhile Iraq had attacked Iran resulting in a long war which ended only in August 1988. There followed three presidencies, the first one (1989-1997) led by a pragmatist-conservative alliance, the second one (1997-1985), led by a reformist-pragmatist alliance, and the third one since 1985 led by a fundamentalist-conservative alliance, which increasingly tended to be more fundamentalist and less conservative. What the forthcoming presidential election of May 2009 will have in store for Iran no-one can predict with any degree of accuracy in that most unpredictable of modern societies.

Currently based at the University of Oxford, Homa Katouzian is a member of the Faculty of Oriental Studies and the Iran Heritage Research Fellow at St. Antony's College, where he edits the quarterly journal Iranian Studies. He is also a member of the Editorial Board of the Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

| Recently by Homa Katouzian | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Private Parts | 3 | Nov 04, 2009 |

| Beyond the Old and the New | 4 | Sep 04, 2009 |

| Wither Iran? | 28 | Aug 12, 2009 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

What's the next revolution going to be like?

by Javid Iran (not verified) on Sun Feb 22, 2009 09:43 PM PSTEver since sword swinging barbarians imposed their barbaric culture and religeous cults on Persia, Iran has had many such revolutions, one after another.

Thanks to the Islamic Revolution however this time mollahs have finally unmasked themselves and have shown their true face: The hatred of everyting Persian. There is no other example better than this that IRI President's office is located on Palestine Ave. instead of Korosh Ave.

The next revolution will be a revulsion against Islam and will take us on the road back to the grandure of our Persian heritage.

Best theory so far

by Ari Siletz on Sun Feb 22, 2009 08:49 PM PSTmonopolized not just power, but arbitrary power--not the absolute power in laying down the law, but the absolute power of exercising lawlessness."

Looking to the future, Iranian leaders (IRI or otherwise) would be well advised to study your analysis of the relationship between state and society in Iran, so as to understand that it is the arbitrary rule tradition we have been trying to overthrow since 1906.

What "ganselmi" is really saying (aka Pahlavist revisionism)

by 1965Tehrani (not verified) on Sun Feb 22, 2009 08:31 PM PSTHow dare people criticize and revolt against the Beloved Aryamehr? Would "ganselmi" ever accuse Aryamehr (with his neverending cult-of-personality and enforced king worship) of being a demagogue? For my part, I have never worked for or received money from any organ of any Iranian regime. What about revisionsts? Were they members of the Rastakhiz Party, infomant for SAVAK or an employee of any organ of the Shah's regime or the Pahlavi Mafia (headed by twin siblings Mohammad-Reza and Ashraf).

enough already please

by shirazie (not verified) on Sun Feb 22, 2009 06:40 PM PSTover analyzed, re written, re blamed. it happened so get on with it.

as the right winger of all time " Roland Reagan" said Iranian Revolution was a true people's movement.

Beware the ones who want to bring you liberty from their cozy Virgina, Texas or outside Iran homes. They have another agenda.

when Iranians of Iran (Not Los Angles) ready, they will get ride of the Mullahs -

Enough of these Iranian Richard Perles

Revisionism...

by ganselmi on Sun Feb 22, 2009 05:14 PM PST...or, another left attempt to refuse responsibility today -- some thirty years later -- for the bitter fruits of the left's delusional complicity with Khomeinist insurrection.

Mr. Katouzian, the dialectics of the '79 revolt were not defined by the coming together of diverse social forces over against the "arbitrary" state but by the capacity of demagogues of the red and black variety to deceive an ungrateful nation.

As Juan Donoso Cortes, speaking of another wave of demagoguery, reminded us some 150 years ago, "people are not accomplices in such scandalous crimes. The people are victims, not executioners. The people ask for liberty, and the demagogues give it to them. In the dictionary of the demagogues, the word 'liberty' is synonymous with despotism and force, while in the dictionary of the people it is synounymous with reparation and justice." Our demagogues, like those Donoso Cortes decries, "know how to read the dictionary of the people, but the people don't know how to read the dictionary of demagogues."