به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Kabul Days (16)

by Hossein Shahidi

01-Jun-2012

PARTS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

Iraq Body Count

Friday, 18 April 2003

Today, we went to the Thai restaurant down the road from our guest-house. It’s just opened - a small house, the ground floor having been turned into the kitchen and dining area. A small courtyard with some grass and a few trees provides a nice view. The food is very tasty, meat as well as vegetarian, and pricey: 15 dollars per head for a meal and coffee/tea. It is described by some as the classiest restaurant in Kabul, in preference to Shandiz, and I’ll tell you about this later.

The restaurant, called Lai Thai, has been set up by a Thai lady called Lalita who has been following the UN from East Timor to Kosovo and now to Kabul, and has a regular clientele of ISAF soldiers. Afghan society, including ministers, also go there. Lalita is now trying to open a restaurant inside the American base at the Bagram airport, about half an hour’s drive from Kabul, where she can work free from all taxes.

Before the meal was served, I got up from our table to have a look at the Thai pictures on the wall over on the other side of the dining hall. Before I had reached the other side, a European man sitting at a table over there called me, or rather waved at me. I looked at him and recognised Dominic Medley, one of the World Service Training Department’s overseas trainers. It turned out this is his second training visit to Kabul and he’ll be running courses for Radio Azadi.

Dominic’s first visit to Afghanistan lasted nine months, during which he and a friend of his prepared a book called The Survivor’s Guide to Kabul, which will be published soon. That makes him a good judge of Kabul’s hotels, hostels and restaurants, in which capacity, I guess, he criticised our glorious kabab temple, Shandiz, for serving too much meat. Parvin had already made this point, and we now think we should bring it to the attention of the manager of Shandiz, Mr Pahlavan.

On our way to the Tahi restaurant, we had to stop at an intersection to give way to a company of bulls, about ten. They passed us by leisurely and confidently and, without making any effort, managed to shake and rattle our 4x4. Ehsan, our driver and resident agricultural expert, said the bulls had been imported from Pakistan to be sold as meat. They eat so much that no Afghan farmer could afford to keep them. In Pakistan they are fed sugar beet, which is called lab-labou in Afghanistan, but is not grown here as much as it used to in the past. Ehsan said the company of bulls that had just passed by us may in fact have been on their way to a nearby military base where they would be turned into human food.

Water shortage must be one reason why sugar beet growing has gone out of fashion in Afghanistan. War, mining and the much higher profitability of the opium poppy are other factors affecting agriculture here. Fighting still goes on, in the form of sporadic and scattered clashes in the north and west, and larger battles against the Taliban-Al Qaeda in the south and east. Mines keep claiming 120-150 lives or limbs every month, a figure which the UN says is one half of what it was in the past, but still a huge catastrophe.

This year, there is much more water than at any time over the past five years. It rained today again, from morning till late in the evening. So maybe there will be more fruits, grains, grass and fodder this year. Maybe even more lab-labou.

Saturday, 19 April 2003

In the morning, I dropped in on my former BBC colleague and Kabul tour guide writer who’s started a course at Radio Azadi, just down the road from us. It’s an impressive set up, with good office space and equipment and a team of young men and women journalists. Their programmes are broadcast from Prague, but there’s a lot of input from Kabul.

The course is funded by the US Congress and will run for several months, with a number of intakes of trainees. At the end of it, the best trainees will go to the US for a two-month advanced course. They started the day with computer training and will then move on to radio production. I’m meant to go back on the last day of the course when they make a half-hour programme.

In the afternoon, we had the second session of our Afghan TV course, discussing editorial values and writing techniques. The men on the course are experienced journalists and it is not easy to keep them interested, especially since they, like many of their colleagues, are unhappy with their pay and working conditions. Their salaries are around $40 a month for a forty hour week. As if that were not difficult enough, the government recently cancelled the civil servants’ transport service to save money.

This has meant that many women have had to give up their jobs because public transport is limited and in a poor condition and many of the young men who use it are rude and unhelpful at best and could even harass the women. The situation is not much better for men either, because a journey which would have taken them half an hour on an office bus could now take up to two hours.

At the same time, some Afghan radio and TV broadcasters, male and female, have gone over to the UN or foreign organisations where the pay is ten times higher. Given this state of affairs, perhaps it is too much to expect people to get enthusiastic about a two-hour a week course with no clear outcome. Still, I have to try and remain hopeful.

Next week, I’ll be starting another course at Afghan TV, this time news writing in English. There will be six participants, chosen by the head of the organisation and his deputy. They were putting down names during our meeting with them at the office – all men’s names. I intervened and asked for a fifty per cent female representation. It was agreed by the head of Afghan radio and TV, a very nice man who last week spent more than an hour telling us about the organisation’s problems – form the lack of funds four months ago to build toilets for female staff in the new premises, to the cutting off of the transport service to save the government around 5,000 dollars a month, and to foreign organisations giving them equipment that they could not use, listed at exorbitant prices which would feature on the donor’s statements as major foreign aid.

Later this week, I’m starting a course at the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, aimed at helping senior officials understand the media better and get their message across to them. Here, as in Iran and many other countries, government officials believe the way to survive is not to let the media get close to them. Any report is highly likely to cause controversy about the organisation that is being covered and officials don’t want to spend their time defending themselves against their critics, rivals or enemies.

Some journalists, on the other hand, believe it is their job to bring the government down, rather than perhaps help it bring itself down. So they ask aggressive questions and write inflammatory, perhaps inaccurate, reports that don’t help anyone. The problem is all the more serious here because the outcome will not be limited to someone losing their seat in parliament or being passed over for promotion, but there could actually be bloodshed.

This is why part of the course will involve ministry officials and invited journalists talking about their respective professions and approaches, with the hope that while the journalists go on asking tough questions, they will be seen as citizens who are doing this for the benefit of the public. The officials could then be more open and involve the public more actively in the way the country is run. Yes, you have seen, heard, read, or thought all of this before and there’s no guarantee that it will work. But we can only try.

Today I made another discovery: our neighbourhood, Wazir Akbar Khan, is named after an Afghan military leader who in 1841 rose up against Afghanistan’s ruler, Shah Shoja’, who had been brought to power by the British, replacing Wazir Akbar Khan’s father, Dost Mohammad. The forces led by the 17-year old Wazir Akbar Khan defeated the British troops and reinstated Dost Mohammad Khan.

As a neighbourhood, Wazir Akbar Khan has always been the residence of the Kabul elite, including the Taliban when they were in power. Many of its Afghan inhabitants are now living abroad, others in other parts of Kabul, having rented their houses to international organisations. So the Kabul elite is now mainly made up of foreigners. It does not look very sustainable.

Kabul is now colder than London, I hear. It was raining for much of the day, and it was also very cold – so cold that several people have put jumpers on, including a British colleague in another UN office. I had thought that if anyone were not to feel cold here it would have to be a Briton.

Sunday, 20 April 2003

This has been one of the days when not much happened – not much outside our office, that is - except for the rain that has turned into floods in the Shamali plains, destroying houses and farmlands. Three children are missing, but 200 families have been rescued by helicopters. The poor people of Shamali: first they had the faction fights; then the Taliban; then drought; and now the floods. Still, too much water is probably better than too little, as least here, where food is in great demand.

Speaking to our guard Ashraf this morning, I learned that his family and most other people in this city cannot afford to eat fruits – and on our dining table there are four large dishes full of different types of fruits. Meat they eat once or twice a month. The rest of the time, it is bread, potatoes, vegetables and rice. The gentle soul that he is, Ashraf was apologetic about people eating a lot of bread, saying Afghans eat too much. When you have very little else, what can you do but eat lots and lots of bread?

We started the day with a UNIFEM presentation at the weekly UN briefing. Our consultant from the University of London, Professor Deniz Kandiyoti, spoke about her research into women’s livelihoods in Afghanistan which shows a great variety of roles for women in the household economy and much greater power and influence than is commonly assumed. It was a short, clear presentation followed by a couple of good questions and very good answers. Economics and economic analysis is not, sadly, something that most journalists eagerly pursue, being much more interested in the ding-dong of power struggles. Women’s economic power is even less ‘sexy’ as news. Still, as UNIFEM’s first major media activity, it went very well.

In the morning, the news story that grabbed me most on the BBC news website was about a British soldier who was shot dead in Mosul and there’s now an investigation to find out if he had been given the full body armour which may have protected him. He was the first British soldier to be killed ‘in action’, the rest of the casualties having been inflicted by ‘friendly fire’. One click away, the Iraq Body Count website – www.iraqbodycount.net - was displaying the number of the Iraqi civilians killed by the American-British forces as between 1,878 and 2,325. No body armour or any other kind of protection and no investigation – at least not now.

Monday, 21 April 2003

Today, one colleague was complaining that life and work here were all the same, one day being exactly like the previous one, meeting the same people at work, and doing the same things at home. I found the complaint interesting, because for me, as I’ve told you repeatedly, no two days have been the same. Every day has brought new people, new ideas and new problems to solve – or rather, new puzzles, because none of them have been dispiriting or frustrating, so I could not really call them ‘problems’.

For my Afghan colleagues, though, the situation can obviously be very different. For a start, they are far too young to be interested only in learning about Afghanistan’s history, even though they may know much less about it than they think they know, or ought to know. Gender makes a difference, with male colleagues seemingly more tolerant of the circumstances than the female ones. Being male does allow you to go around much more easily, while women have to stay much closer to home, under the protection of their men.

It was the second time I was hearing such a complaint – the first time it was about life being ‘a repetitive cycle of 8-to-4 days’ – something which I had not expected to hear outside of metropolitan cities such as London. It was a good reminder that as ‘internationals’, we not only have more electricity, fruits and food than our Afghan colleagues, but also a greater of sense of purpose derived from our employment. In addition to our immediate material advantages, we also have better career prospects, or a sense of ‘mission’. Our Afghan colleagues, I guess, have seen enough ‘missions’ carried out by various powerful groups in their land to make them sceptical of all of them.

As far as a career is concerned, it would be strange for them to contemplate staying with the UN forever. At some stage, they would have to or would want to move on to something more ‘national’ – but what is that going to be, with what pay and what prospects? What’s even sadder is that as émigrés/refugees/exiles in Pakistan, at least those Afghans who could afford it would have had access to a much more active social life.

Today, as part of our preparation for the series of courses that we’re meant to run, I collected newspaper reports about women and children. One was the sad account of a 16-year old bride who’d been set on fire by his 20-year old husband – in full view of in-laws who came to her rescue only after she had been severely burned. According to the poor girl, the man had poured fuel on her and lit it after she woke him up and asked him to make fire so she could make breakfast for him. I have seen other reports of young women in Afghanistan, and in Iran, setting themselves on fire in protest against forced marriage.

A far happier report was about a woman doctor who has spent the past decade of war working in a maternity hospital, although she could have left Afghanistan at any time for a ‘better’ life abroad. Another report was about the military industries which employ about 180 women, and the same number of men, making uniforms and other products. And another was about a 35-year old single woman who works as a radio drama artist, having been a broadcaster since the age of 9. It was fascinating to come across such a wide range of experiences only in one afternoon. Following up each one of them is guaranteed to teach us much more about the reality of women’s lives in Afghanistan.

In the morning, I was going through the latest edition of the satirical magazine, Zanbel-e Gham (the basket of sorrows), which is not typed but hand-written, because the editor/publisher believes this is how satire should be presented. The dominant theme was the shortage of electricity, complaints about which came in numerous verse and prose pieces. There were references to Cherkestan (the dirty land), a derogatory name for Pakistan (the clean land), which is held responsible for much of the misery in Afghanistan.

This being the Nowrouz issue, one of the funniest, and darkest pieces, was an editorial advising all citizens that they should mark the New Year by cutting down whatever trees have survived in Kabul. If the trees stand, the editorial said, chances are that municipality staff who are busy fighting unscrupulous shop-keepers would not have time to water the trees and they would dry. If they were watered, on the other hand, their leaves could be eaten by the sheep and goats that roam the city. Therefore, the best thing to do would be to uproot any remaining trees and thus welcome the arrival of spring.

Considering this has been a rainy spring and some tree planting is actually going on, it is possible that the editor, Mr Sargardan, or ‘wanderer’, is feeling less pessimistic now than when he wrote the piece. I hope to see him and find out in the near future.

***

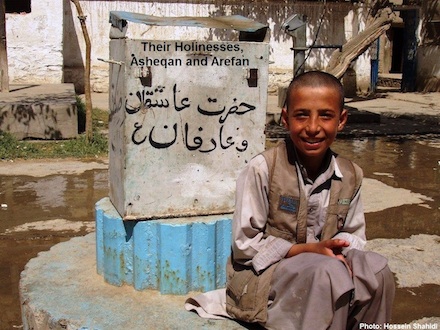

Note: The title of this section of the diaries was chosen to record the passage of one month since the invasion of Iraq, one of the greatest follies of mankind in recent times. As an anti-dote, the pictures are those of a small shrine in Kabul, known as the resting place of two brothers, Asheqan (Lover) and Arefan (Mystic), grandsons of the 11th century pir or sage of Herat, Khajah Abdollah Ansari. The shrine was peaceful, bright, pleasantly decorated and well maintained - all the more impressive, considering that Kabul is still scarred by many years of destruction and bloodshed. For more about the shrine, and other attractions in Kabul, see Kabul Municipality’s website.

| Recently by Hossein Shahidi | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Welcome to Herat | 3 | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (38) | - | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (37) | 1 | Oct 05, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |