به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Kabul Days (34)

by Hossein Shahidi

22-Sep-2012

PARTS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

Please, God, Do not Bring Spring Back

Friday, 4 July 2003

At about the same the time that Agha Sarwar was due to have arrived in Quetta, there was the horrific news of more than 40 people having been killed and more than 60 wounded in an attack on a mosque in the city. It is very unlikely that Agha Sarwar could have been hurt, but the city is going to be very tense and I cannot wait for him to come back.

The good news is that the mother of three, Shakila, has had a successful heart operation in Pakistan. This was made possible by help from people around the world, including one lady from Afghanistan who paid $1,800, nearly one third of the costs of her operation. This seems to have been the first time that a women’s group here has raised funds on such a scale. They are very pleased with the results, and I hope others will learn from their experience.

I have been suggesting to women journalists that instead of going round various international organisations to ask for money, they should appeal to their readers. The journalists tell me that such things are not done in Afghanistan. Quite an odd response, I say, considering that newspaper publishing by women was also ‘not done’ in Afghanistan, but they are doing it now. So why not raise funds as well?

After a longish, but quiet and productive, day at the office I went to an engagement party in Kabul, the first such experience since I got here. The young girl is a translator who’s been helping us for several weeks. Her father works in another UN organisation. The young man lives in London and when the two get married, probably next year, the young woman will also go to Britain. The young man’s father is a prominent lawyer and political leader, with two wives, one here and one in the US, who between them have given birth to 11 children.

The marriage seems to have been arranged by the parents, although one friend of mine who is related to both families – they are relatives – said they must have asked the young man if he was happy with their choice of bride for him. I asked if the young woman had had a say in the matter. The answer was that she must be very pleased with the fact that she will be going abroad. So the young man is marrying a young woman, but the woman is in fact marrying London.

Seven hundred people had been invited to the party, and a similar number are going to be invited to the wedding. The party – in two halls, one for women and one for men, with one live band in each room – started at 5pm, but by 6:30, when I had to leave, only a small fraction of the guests had arrived. Music was playing and people seemed very happy. There were young men in very smart suits, as well as very old men with white beards wearing turbans, who did not seem to mind the very loud music, although some of them stayed very briefly. The party was meant to go on until 10pm, with dancing after dinner. Our security rules forbid us from staying outside beyond 9pm, so there was no way I could have joined the festivities.

The huge costs of marriage are one of the issues that come up regularly in discussions of women’s condition in Afghanistan. Many complain that they cannot get married because they cannot afford the costs of a party, in addition to the dowry that the girl has to take to her husband’s home, and the cash that the girl’s family have to get from the bride-groom’s family to agree to the marriage. Some say these costs should be limited, or even banned in the Constitution. Others say that if a girl gets married without such ceremonies, she is going to be the subject of ridicule and insults by others who would say she was not worth anything.

My friend who was informing me about the backgrounds of the two families also told me, when we were having a conversation about learning English, that many years of his life had been wasted because of his belief in his religion and country, for which he had sacrificed his youth. He had been offered the chance to go to Britain, where he would have had great opportunities for education on grounds of being very smart, but he did want to leave his country behind and stayed on to work for his political organisation. Having been told that the sons of the leader of his group, and those of others, were in the West, he had said this could not be true. Now, he says, he knows that that was true and that people like him were taken advantage of.

Disappointed with the religious leaders and their pronouncements, he now wears a very short beard, waiting to see if anyone dares criticise him for it. He also spends all the time and money he has on the education of his six children, between the ages of 3 and 16, four of them girls. Three were born in Kabul and three in exile in Pakistan. ‘We had no plans,’ he tells me, ‘but were going from one place to another. So these children kept coming along.’

It’s tough being a girl in Afghanistan, and tough to have four girls as your children. Still, my friend is yet another of the many brave souls I’ve seen here who give you confidence about the future of the human race. If they are indeed helped by the rest of the world, his children may well get what he was deprived of in the many wasted years of innocence, deception and violence.

Saturday, 5 July 2003

Eighteen people, including two female suicide bombers, have been killed in Russia; about 10 people have been killed in Iraq; and two ISAF soldiers have been wounded, apparently by a mine, near Kabul. Luckily, for the first time in a very long while there have been no reports today of anyone having been killed in Palestine.

This morning on our second visit to Kabul University, there was great progress on setting up a course for working journalists. We will have some of the best journalists in Kabul as our guest speakers and the participants are also expected to be among the best. It should be a very interesting experience.

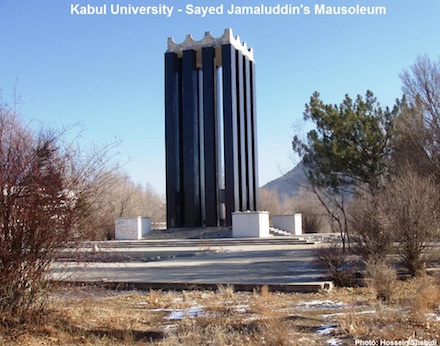

After the meeting, we drove through the campus to the tomb of one of the earliest of champions of Islamic unity and modernisation of the Moslem world, Sayed Jamaluddin Asadabadi, also known as Al-Afghani. Sayed Jamaluddin’s origins are the subject of one of many disputes over the ownership of cultural heritage between some people in Iran and Afghanistan. Many in Iran believe that the Sayed was from Asadabad, near Hamadan, in western Iran and that he is buried there. Here in Afghanistan, he is believed to have been born in 1838, in another Asadabad, in the heavily Pashtun province of Kunar in eastern Afghanistan.

Whatever his birthplace, he did spend a lot of his life in Afghanistan before going to Iran where he failed to get the Qajar king interested in a pact among Moslem nations to fight British imperialism and regain their past glory. He then travelled to Russia and to Western Europe, including Britain, before going to Istanbul to try to convert the Ottoman Caliph to the cause of Islamic unity.

You don’t need a lot of historical knowledge to figure out that the Sayed did not have much success in his quest, but his bold vision did have an impact on the anti-authoritarian thought in Iran which resulted in the 1906 Constitutional Revolution. He also had long lasting intellectual influence in Egypt, leading to the creation of the Moslem Brothers in Egypt which is still a major political force in much of the Islamic world.

He died in 1897 in what today is Turkey and, according to the Afghan version of history, his remains were brought to Kabul in 1944 and were buried in a place called Ali Abad. This area was later turned into Kabul University.

I had read about Sayed Jamaluddin’s mausoleum in Kabul University in a report by a woman journalist from Iran, Jila Bani-Yaqoub, who had come here for the Iranian newspaper Hamshahri. The mausoleum is an impressive building: you go up three steps to reach a platform at the centre of which there is a big tombstone, on top of it a marble slab with beautifully inscribed Qoranic verses. Around the tombstone, there are twelve rectangular columns, each about twenty meters high, covered in black marble. At the very top there is a dome. Three slabs of marble hang on three sides of the structure, giving the Sayed’s brief biography in Persian, Pashto and Arabic.

By the standards of West Kabul and some parts of the University compound, the mausoleum has survived the wars in this city unscathed – but only by those standards. At the very least, the wars stopped the structure from being completed and maintained. There are also bullet holes everywhere, and parts are missing from each of the biographical marble slabs. One of the slabs, on top of the tombstone itself, has been broken into pieces, but almost all of them are still there.

Now that there is some kind of non-war in Afghanistan, the mausoleum is being renovated, funded by the United States. It is unlikely that the Sayed would have looked very kindly at what the United States has done in Afghanistan over the past two decades or so. Therefore, it is quite possible that his soul is not enjoying the renovation all that much.

I personally would much rather see money spent on renovation – even if it’s the renovation of graveyards – than on weapons that send people to their graves. Also, for all we know, the Sayed may in fact be buried in Hamadan and some other deserving spirit is getting the attention that it probably did not get while it was captive in someone’s body.

***

On Sunday, 6 July, a team of surgeons in Singapore’s Raffles hospital will try to separate two Iranian sisters, Laleh and Ladan Bijani, who were born 29 years ago with their heads attached to each other. They and their parents have made a great effort and one hopes that their courageous decision to undergo the operation that has been carried out successfully only once 16 years ago will meet with success.

Sunday, 6 July 2003

After several days of humidity piling up alongside heat and dust, it finally rained last night and cleansed the air and the streets for a few hours. But there was also a bad side to this. Further away from central Kabul, one neighbourhood was flooded for the first time in 8 years and fifty homes, with more than 100 inhabitants, were badly damaged. Fortunately, no lives were lost. A friend of mine explained that rain at this time of year is also bad for agriculture, because all the harvesting has been done and the rain simply messes up the fields.

Two funny, but also promising experiences: Firstly, I went to television this morning for the last session in the English news writing course. The class was meant to have been yesterday, but I had called a TV official on Thursday to say I could not make it and ask him to tell the participants to come in today instead. When I got to the classroom, there was no one around. I was told that the participants had come in the day before, waited for me for a while, and then gone. I asked if they had been told that I would come in today. ‘No, they had not.’

Disappointed, I made my way back along the corridor but ran into one of the trainees who told me someone else was also coming along. She then went to call the others and in about five minutes five of the six participants were there. The sixth person who was away on a trip had sent in her assignment, and the evaluation of the course that I had asked everybody to write. They were all very positive about the course and said it had helped them write and speak in English, read the newspapers, and listen more to news on radio and television. They were very kind to me personally and gave me two pens as gifts, which really embarrassed me.

In the afternoon, we met with the producer of the Woman and Society programme which last week was meant to have had a 20 minute segment on our economic conference. In fact the entire programme was 20 minutes, instead of the usual 30, and the coverage of the conference was really miserable, even though we had sent cars over to bring the crew to the conference and take them back home. After some questioning, the producer said the one of the tapes on which he had recorded scenes from the exhibition had broken on production day. Another tape had been recorded over and a third tape had not been used because he had not found the time to copy it onto a format that could be used in the studio.

In other circumstances, there may well have been a shouting match in the conference room and the producer may well have been sacked on the spot. Not here, though, because we all know the background to such errors and they cannot all be described as personal incompetence. So we all controlled our nerves and decided to meet tomorrow to see how we can change the team’s working habits. At the very least, one hopes, they could try to avoid recording over their own tapes or breaking them, and find one hour of free studio time during one week, which is possible even in Kabul, to dub a tape from one format to another.

The male producer has so far insisted on having sole control over production and has shown no interest in getting women’s views about what should go into a programme that’s meant to be theirs. This may now change, because during the meeting one of the female presenters finally summoned the courage to tell him that every week he gets her to read the same script and that she had read some passages eight times. The producer’s defence, that those passages were about women’s high status and had to be repeated, got nowhere. At tomorrow’s meeting, there are going to be several women and I do hope that we can come up with a new format.

Before our meeting, the producer told me that for the next programme he was going to have a cookery slot. Why, I asked, not a whole programme devoted to cookery, so men could also learn, rather than use up some of the time of the only women’s programme? He said this was because he had had letters from women asking for cookery lessons. I somehow doubt this, but did not press the point. Instead I asked how long the cookery slot was going to be. ‘Two minutes,’ he said.

‘Have you ever cooked?’ I asked. He said he had, and mentioned some food with potatoes. I said it would take more than two minutes to peel a potato, and it would not be possible to teach anyone any cooking in that short time. By then we had reached our destination and I could not pursue the matter any further. I’ll let you know if my friend does come up with his two-minute cookery wonder.

Monday, 7 July 2003

Talking about the disappeared journalist, Mr Mahdavi, yesterday, I forgot to mention that he had studied at the Qom seminary for several years, as well as graduating in physics from the Qazvin International University in Iran. He is also a poet and won the top award in a poetry competition in Iran several years ago.

By accident, a friend gave me a collection of poems by young Afghans, published in Iran nearly a year ago, with two poems by Mr Mahdavi, who’s 33 now. One is a simple, rhythmic ‘letter’ to some unknown friend, about the pains of poverty and exile.

The other one is a much more powerful account of the destruction of soul and body, with the title az dast-e khod, which can mean ‘with one’s own hand’, or ‘from one’s own arm’. Reading it this afternoon, I could not help feeling that it was a good description of the poet’s present conditions.

How lonely I am today, how sad

I see a man like myself, hanging from the gallows

I think it’s probably one melancholy, soulless Friday evening

And I feel like a heavy, wandering mountain

Where art thou, my friend at my moments of happiness and fervor?

See how I have fallen, while riding a wooden horse

Only a moment ago, a moment before I died, I was telling myself

I must pray to Allah to forgive me for the sake of your eyes

Even though I’m a non-believer

Yes, I have fallen from my own arm, from a very big height

And I know that my shameful tale has come to an end

I myself carried my own corpse to the grave

I myself cried when I was being washed

When I was being buried

And when I was being mourned

This is obviously a sad poem, but the book also contains many mellower ones, both in classical and modern styles. They are among the best Persian poems I have read for a very long time. Some of the poets are now back in Afghanistan. One of them, Shahbaz Iraj, who worked on Persian literature in Iran for a while, reports for the BBC’s Persian Service. Another, Khaleda Forouq, is among Afghanistan’s leading poets and publishes a very good feminist journal called Sadaf, or Shell.

A third, Mahbouba Ebrahimi, studied health-care in Iran and has written my favourite poem in the collection, Bahar (Spring):

Once again, spring has arrived

And birds know that war too will once again arrive

Plains and hills and villages

Will once again become nests for rifles

Once again, spring has arrived

And my brother has left behind our field, our harvest and our flock of sheep

Feeling tired, he has made it to the mountains

He has gone and left behind a deep sorrow

Once again, by the spring, the two of us

Spoke of stars and spring

Last year’s was the first spring

With so many graves in the village

This spring too, once again

The trees must wear new clothes

Lucky trees, for they are not like us

Who have to wear burial shrouds for Nowrouz

O children of the village, pray!

Pray, so God does not bring spring back

So there is always snow everywhere

And no one

Can bring war to people’s homes

***

| Recently by Hossein Shahidi | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Welcome to Herat | 3 | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (38) | - | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (37) | 1 | Oct 05, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |