به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Kabul Days (26)

by Hossein Shahidi

09-Aug-2012

PARTS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

Wheat, Saffron, Opium

Friday, 30 May 2003

Jeremy Bowen’s report on BBC TV showed Tony Blair in Basra, which must have been considered the most secure part of ‘liberated’ Iraq for him to visit. Mr Blair told a small group of the British troops that while there had been a dispute in Britain over ‘the wisdom of my decision’ to attack Iraq, there was no dispute on the soldiers’ professionalism’. He also went to an Iraqi school - as Jeremy Bowen put it, ‘most of the Iraqis Mr Blair met were under ten’ - and held one up child in his arms, visibly not very comfortably or affectionately.

At the office, the website, Iraq Body Count, gave the latest figures for the civilians killed by the professional American and British troops as ‘Minimum 5428, Maximum 7044’. The editors of the website are now compiling the list of names of the innocent Iraqi victims of Messrs Bush and Blair’s war on their land and have so far established the names of 100 people, and the ages of 80 of them. Twenty-two, or more than a quarter of these, were between the ages of ‘baby’ and 11–the same constituency that Mr Blair tried to enlist during his visit to Iraq. [On 12 February 2012, the website put the number of ‘Documented civilian deaths from violence’ between 105,242 and 114,940.]

After lunch, we all went to the Iranian trade fair which was quite impressive and full of visitors. The busiest stall belonged to the Iranian Radio and Television with books on everything from electronics to poetry. Seeing no one at the Razi glue and chemicals stall, I asked the representative why no one was glued to his display. He said there had been so many visitors earlier in the day that he had had difficulty getting them unstuck. He and the representatives from other companies said they were sorry they had not brought along more of their goods to sell. He had sold out almost all he had brought along, with the exception of a few cans of domestic insect killers that we have now booked to buy to deal with the army of cockroaches that have the freedom of our kitchen after 10pm.

The representative of Iran’s biggest vehicle manufacturer, Iran Khodro, was sitting all by himself, sipping tea in a stall which had nothing but a few leaflets and posters with pictures of cars. A few Iranian made Peugeots, with Iranian names, were on display out in the open space, alongside a massive combine harvester, but the gentleman said he did not think his company would have a market for its cars in Afghanistan. Iran Khodro’s top of the range car goes for $9,000, while a very good second hand Toyota could be bought in Kabul for $5,000. Very few people are likely to pay the difference just to have a brand new Iranian-made car, especially since they can probably get its French made version for about the same price, through Dubai.

Iran Khodro might have a better chance with buses, which are in great demand in Afghanistan. Up until 1992, Kabul had 1,000 buses and a few lines of trams, and some woman drivers. During the wars of the past 11 years, the trams have been destroyed and their scraps are now heaped at the main station. The electric pylons that used to power them are now standing bare alongside the street, with all the cables, as well as lots of other electricity cables, cut off and taken away to be sold for copper. Over the same period, the number of buses has been reduced to 300.

The bus company says it cannot possibly meet its costs, let alone expand, unless it receives subsidies from the Afghan government. The government says its funds are donated by foreign countries, through the World Bank, with the condition that none of it should be spent on subsidies. Unable to charge the poor passengers more than 1 Afghani (just over 1p), the company has been leasing its buses to government ministries who can pay more. But this cuts down the number of buses available for the rest of the public, creating a vicious cycle.

The third Iranian businessman I spoke to represented a chinaware factory, with a display of 56- and 106-piece sets, as well as individual items. The firm, Maghsoud China, is based in Mashhad and has now opened an office in Kabul. The company rep did not appear very excited about the Afghan market, saying they had over-estimated the Afghan people’s purchasing power, but added that about 20% of the people of Kabul could be counted as his firm’s potential customers. The firm also faces competition from China itself, where the wages are even lower than in Iran. In contrast to the few people looking at the chinaware, the stall next door displaying melamine dishes, at much lower prices, was brimming with visitors.

Most Iranian business reps were male, but there were a few women, most of them at the heavy industries or pharmaceutical stalls. The visitors included many women and school girls, and a group of Chinese women, with black glasses, flowing hair and no scarves, who attracted a lot of attention, and had a crowd following them wherever they went.

The last stop on our Friday adventure was the military base of the International Security and Assistance Force, ISAF, with about 5,000 soldiers from around 30 countries – nearly half of them from Germany - who are in effect Kabul’s police force. So far as I know, they have not been involved in any acts of violence against Afghans. But they have come under attack repeatedly, especially after American attacks such as the one two weeks ago when American soldiers at the US Embassy shot dead three Afghan soldiers inside the Afghan army garrison across the street from the embassy.

Many of the American troops, who make up 8,500 of the 11,000 ‘coalition’ force fighting in south and east Afghanistan, are based at the Bagram Air base about 30 kilometers outside Kabul, where they have a store which is visited by other foreigners. The ISAF base is a small military town in the grounds of Afghanistan’s former military academy on the edge of Kabul. It has a store with very low prices charged in Euros - no other currency is accepted – open to few people other than ISAF personnel. A bottle of brandy sells for 4 Euros, and a box of Danish biscuits for 2 Euros. Another ISAF shop, outside the base, lets in more customers and has a wider variety of goods – from hair and shoe brushes to salmon, cereals and all types of beer, wine and whiskey – but also charges much higher prices, in dollars.

We came back with some salmon, cottage cheese and blue cheese – which we had for dinner - and cappuccino packets that we’re going to have for breakfast. If you think this is too luxurious, let me tell you that we had lunch at the Intercontinental Hotel, sitting on the balcony, with lovely weather and a beautiful view of the mountains. For added attraction, we had two ISAF helicopters flying by pretty low – perhaps going back to the store at their base for some goodies.

Saturday, 31 May 2003

Two intensive training sessions and an hour of video watching left little time for any sight-seeing or broadly-based studies. But the sessions themselves produced lots of interesting observations and thoughts.

The first workshop with a group of TV staff focused on news writing in English. This is the group who said, when I met them first two weeks ago, that they did not read newspapers, watch TV news, or listen to news on the radio, and did not know much about what was happening in Afghanistan. This week too none of them had read the English language Kabul Weekly that I had recommended to them. The explanation offered by one of them was that they did not have a newspaper shop nearby and there was no one who could get the paper for them.

I asked them how many people worked at the TV station. ‘1,700’, they replied. I said the newspapers were on sale at a distance of about 25 minutes walk from the station. They were then persuaded that it was possible for them either to get the paper themselves, or to arrange for it to be collected by another staff member. Next week, they promised, they would have the paper.

On the plus side, when I asked the group to write a page about the most important event they had witnessed or heard of during the past two weeks, three of them wrote reports about very important national events. One of these was the memorized reproduction of a BBC report that had been carried by the Afghan press. Two other participants wrote interesting pieces about their children. And the sixth wrote an account of a business visit to a nearby town. In spite of inevitable flaws, all were understandable, which was impressive, considering this was the second time they were writing something in English to be read out. The first exercise, two weeks earlier, had been to write a summary of a newspaper article. There’s a lot to look forward to over the next five weeks.

The return to the office allowed for a very quick lunch before it was time to go back to the TV station for the second workshop: chairing panel discussions about violence against women. Even though the subject had been decided two weeks ago, no member of the group had studied it. One person said they had been too busy. Still, we did go through several rounds of exercises which produced very general statements, and the important learning point that research and preparation do really make a difference. Next week, we’ll be discussing education for girls, and the week after that CEDAW, which should be very interesting.

Another quick visit to the office for a cup of tea and some newspaper cutting, before rushing to the Aina cultural centre to see the video footage selected for our 8 March documentary. The most important discovery here related to the person I had seen dancing at the journalists’ union’s 8 March event. Those of you with enough patience to read these notes to the end and sufficiently long memories to remember them may recall that during that event there was an appearance by Afghanistan’s first female singer, Mirman Parwin, now 76, followed by a performance by a younger woman singer – the first such act in more than 10 years – and a little dance by a man.

Well, I learned today that the dancing man, in a suite, with short hair and a hairless face had apparently been a woman. Now, the person who told me this was not sure if this really had been the case, which is rather bizarre since there’s been nearly three months’ time to check this out. The row that developed soon after the event over a woman singing in public could reappear when our film shows both the singer and the dancer.

It should be interesting to see what people say about the dancer in particular. Does it matter if a dancer is male or female if the audience cannot tell the difference at the time? Does it matter if they find out the performer’s gender later on? Does it amount to deception, or is it just clever to present a woman dancer appearing as a man? Is it worse for a woman to dance in public than a man? What is a man and what is a woman?

A whole series of questions about gender relations, resulting from a couple of minutes of tape showing someone rather bashfully stepping left and right and back and forth, to some simple music, on the fourth floor of a rundown but busy shopping mall in the middle of an even more rundown but even busier central Kabul, nearly three months ago.

Sunday, 1 June 2003

Today we visited the north eastern Kabul ara of Kolola Pushta, or Round Hill, named after, well, a massive round hill with a fort on top it; old but now vacated weapons and ammunition storage space underneath; and houses and businesses around it. One such business is paaykoob-e naswaar, or the beating of tobacco with a tool shaped like a paa, or foot in Persian. The mashed tobacco is then mixed with some kind of acidic rock ground to a dust and, if you’re in Qandahar, also with some cardamom. The mixture is placed in the mouth, in front of the teeth, gradually destroying them and, Ehsan says, also blinding the user.

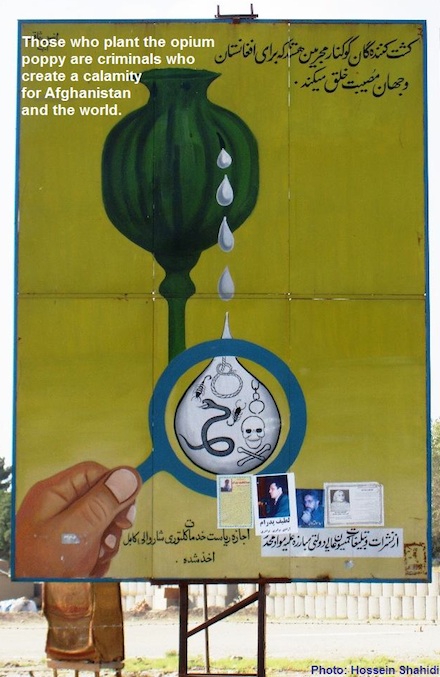

The dangerous substance is the core of a very lucrative business controlled by a network of local monopolies – a minor league mafia. Speaking of the mafia, for several days there have been media reports casting doubt on the efficacy of the efforts to stop the opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan, the supplier of about 75% of the world’s opium. This is the harvest season and violence can be expected between the government agents and poppy farmers.

Much of the media coverage I’ve seen has been supportive of the anti-opium drive, using the moral argument that the plant is a source of trouble for the country and ruins the health of the Afghan nationals too. But this kind of preaching does not have much effect because of the high revenues from the opium trade and the relatively small scale of local addiction – in fact most Afghans could not afford to buy any form of drugs other than naswar.

There are also recommendations that farmers should plant other profitable plants, such as saffron. This advice has not been effective either, partly because it will take a long time for any other plant to be grown in marketable and profitable amounts. Another problem is that while rising opium production can lead to lower prices and higher consumption, keeping the business profitable, it is difficult to see how the demand for saffron could rise fast enough to compensate for any fall in prices that would result from increased saffron production.

The suggestion that poppy framers should plant wheat is laughable. Opium sells for 500 dollars a kilo in Afghanistan, and many, many times more when it reaches the West as heroin. The price of wheat in Afghanistan is about 10 cents a kilo, thanks to the huge amounts of subsidised, surplus Western wheat that is given to the poor Afghans as aid. Afghan refugees even receive free wheat as part of the package that is meant to ease their return.

Another incentive offered by the Afghan government, in fact by the foreign powers backing it, is to offer farmers cash compensation so they stop growing the poppy. As a government newspaper’s editorial said a few days ago, this is in fact an incentive to grow the poppy. If the government cannot reach the farmer, he can sell the crop and get cash. If the government does reach the farmer, he can destroy, or pretend to destroy, the crop and still get cash. A win-win situation.

Incidentally, I learned from our consultant academic, Professor Deniz Kandioyti of London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), that one reason why the opium poppy is so abundant is that most of the farming work is done by women who do not get paid for their labour. So maybe the economic and political empowerment of women will do more for limiting poppy cultivation than all the other methods put together.

Women’s economic empowerment was the reason why were in Kolola-Pushta, to see a building that could be rented as headquarters of the recently established Afghan Women’s Business Council. The four-storey house is well designed and solid, with a beautiful rooftop view of Kabul and its surrounding mountains, behind which the sun was setting gracefully. This and a few other recently built houses were in dramatic contrast to the area’s dominant style of architecture that consists of low, mud-brick dwellings with one or two trees, possibly a well and a hand-pump.

Given a few years of peace, the neighbourhood could become a very modern and expensive part of Kabul. At present, one must have serious doubts about its suitability as the venue for a gathering of businesswomen. The house, being built by a young Afghan living in the West, is about three kilometres from the main road, which is itself pretty narrow and crowded, with very limited public transport.

Distance, though, would be no problem compared to the state of the connecting roads, with surfaces that resemble the face of the moon – when you’re actually on it, not looking at it from the earth and seeing it as the face of your beloved. There are so many potholes and deep and crooked tracks that even the 4x4s have difficulty staying on course. I asked how long the roads had been like that. ‘Since the time of Abdur Rahman Khan, who was our guide’ said the young developer’s mother, with a big laugh. Abdur Rahman Khan’s rule ended in 1901.

My friends explained until a few decades ago, that the whole area had been covered in farms and meadows and had been a hunting ground. Seeing how amazed I was at the quality of the road, Ehsan said not to worry because it would get a lot better in winter. ‘How come?’ I asked. ‘In winter,’ he said, ‘you can come here only if you have wings, and then you’ll have no trouble getting through.’

***

| Recently by Hossein Shahidi | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Welcome to Herat | 3 | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (38) | - | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (37) | 1 | Oct 05, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |