به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

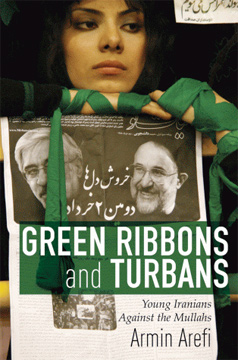

Green Ribbons and Turbans

by Armin Arefi

10-Nov-2011

Armin Arefi is a 27-year-old French-Iranian journalist working for the french newsmagazine Le Point. In 2007 he fled Iran to avoid persecution and imprisonment. In his book, Green Ribbons and Turbans: Young Iranians Against the Mullahs, inspired by his experience in the Islamic Republic, he seeks to combat the usual clichés about the Iranian people and keep the world informed about what’s happening on the streets of Tehran. His contacts in Iran reported to him daily during the protests following the 2009 election, giving him eyewitness accounts as material for this book. He lives in France.

First Chapter

"OH! PRETTY GIRL FROM IRAN! I wanna be your man!” As the song’s bass line kicks in in this north Tehran apartment, a Persian bombshell makes her entrance. Nose job, bleached hair, and no shortage of makeup, she stares hungrily at the men in her midst. Meet Helya, twenty-two years old. Her black headscarf safely tucked away in the closet, she emerges from the bathroom in a lace teddy and a micromini that barely reaches the tops of her legs. On the other side of the room, twenty-four-year-old Omid, his black shirt unbuttoned and gelled hair styled for the occasion, takes one last shot of Aragh Sagi (a local, home-distilled liquor). Tonight’s festivities, a party to mark the twenty-fifth birthday of the wealthy hostess, Hala, are taking place in Fereshteh, a high-end neighbor- hood of the Iranian capital. As proof of invitation to the event, each guest must whisper the password Islam is in danger into the intercom before gaining admission. The number of guests has been kept to a minimum and all belong to Tehran’s rich bourgeoisie. It is party time. Bass thumping, furniture shaking, the guests scream along with the music. “Ahaii. Ahaii. Jooooon.”

“Oh, pretty lady, with your arched eyebrows and sweet, honey eyes,” a deep, soothing voice ripples across the room. Omid approaches the beautiful Helya. She turns her back on him, pretending not to have noticed his presence, and the game is on. “I wanna come to your front door,” the singer continues. Omid circles the young woman, shaking his hips like a pro but being sure not to touch her. “That’s not what I want,” comes the female singer’s shrill reply. As for Helya, she smiles faintly and disappears backwards through the crowd, waving her arms as if they were tentacles.

“I’m gonna talk to your father . . . .” The young man draws closer to his prey, who in turn pouts her scarlet lips, making herself even more desirable. “But that’s not what I want . . . .” All of a sudden, she turns on her heels and Omid finds himself trapped in her arms.

“I’m gonna tell him I’m in love with his daughter . . . .” The two young dancers become one as they move to the beat of the last hit made in Los Angeles, the latest Iranian pop hit, forbidden within the Islamic Republic.

“I want to marry you . . . .”

A few seconds later, the door to the adjacent bedroom slams shut. The couple has disappeared and a dozen others will later fol- low in their footsteps. In the living room stands a large table where chips, yogurt, and salad Olivier (a mayonnaise–based savory mix of egg and potato) accompany bottles of Jack Daniel’s, Smirnoff ($70 apiece), and Bacardi (Islam really is in danger). Access to the kitchen is obstructed by a long line which snakes right out into the living room. Perhaps to try the delicious ghormeh sabzi (a lamb stew served with rice) which is simmering away on the stove top? Not quite : On the countertop, rather, are three long lines of cocaine, which each patient guest will sample in turn. For those who are not interested in this particular treat, the next room along is the ecstasy den. The result of this is a group of four wide-eyed young men who, since sometime earlier, have been talking at alarming speed, planning a dramatic escape from Iran by jumping from the window. At the other end of the large front room, another group sits crashed out around an opium–filled hookah pipe.

The bedroom door reopens and Omid rejoins the crowd, barely taking the time to fix his jeans.

“Welcome to the Islamic Republic,” he laughs. “Paradise on Earth, as long as you can afford it.” Omid forces a smile, for he himself—a student from Tehran—was far from born with a silver spoon in his mouth. He owes his invitation to this dream party to Morteza, a rich friend. Luckily for him his real identity remains a secret, or he would never have had the slightest chance of hooking up with the beautiful Helya; even the evening’s delights, however, cannot cover up his deep depression. His financial situation is dire—he comes from a middle-class family and is still in school—and he still has to complete two years of military service, meaning that he is forced to re- main in the Islamic Republic. This is not the case for most of the young people here tonight. Within a few weeks, a month, or perhaps a year at most, they will all have left the country for the United States, Canada, or Europe, and all thanks to Mom and Dad’s bank account. “We’re sick of this president, of this country. Get out if you can is this summer’s big hit,” Helya laughs. And with that, the beautiful Iranian woman has hit the nail on the head: Since Ahmadinejad’s elec- tion in 2005, her country has become a hell on Earth.

“Ahmadinejad has ruined everything in his path. Everything,” Omid sighs. “You can’t even walk down the street without someone giving you a hard time for the way you dress. My university has been Islamized. Our most prominent professors have been laid off; our best politically–active students have been kicked out; the image of our country overseas has been dragged through the mud. It’s like being back in the first few hours of the revolution.” He downs another shot of Aragh Sagi. The pleasures of the moment are what keep this young man alive. “Everyone is depressed and the only thing we can do is to escape it in any way possible. Our parents have seen another way of life but not us; we’ve only ever lived under the Islamic Republic. We’re really a wasted generation.” He takes a big hit of opium. He may not be a fan of this regime, but the young man knows full well that it will not fall as easily as all that. “Here you can screw, drink, take drugs. But so much as stick your little finger into anything to do with politics, and you disappear.”

If these young people are so vehemently opposed to the regime, then why are they not at least talking about another revolution? The student knows exactly where he stands on that one. “My parents al- ready had a revolution, and we all know what the result of that was. The country has taken a leap back a hundred years in just thirty.” A month away from the presidential election, he is under no illusions. “Everything’s fixed in advance anyway. The vast majority of candidates have been eliminated. Those that remain have been hand-picked by the regime and will help to keep it alive,” he explains, going on to warn against having too much faith in the so-called “reformists,” who themselves are far from what you would call democratic. “Mousavi’s great hope?” he bursts out laughing. “When Mousavi was prime minister, over eight thousand opponents of the regime were executed. Have you forgotten that? He’s from the same mold as Ahmadinejad.” In 2001, he voted for the reformist Khatami and his promises of freedom. “I’m still kicking myself for that to this day. He betrayed us, offered us only superficial freedom, and just prolonged our suffering by eight years. I’ll never vote again.”

All of a sudden, the intercom buzzes. “Police. Open this door.” Cries all around, as girls and guys are pushed towards separate bedrooms before the officers arrive: a lost cause, given that many of the guests are simply too high to understand what is going on. Now there is knocking at the door. “Open up, that’s an order.” Gripped by fear, the party’s hostess opens the door. Unfortunately for her, it is not really the police but, far more serious, four Basiji militiamen in green uniforms. In silence they look at each guest with disgust, focusing in particular on the girls and their out- fits, before shouting, “Whores . . . infidels . . . what is going on in here?” Apparently, this is the first time they have attended an event quite like this one. Amir, one of the young men present that evening, tries to calm things down. The youngest Basiji walks up to him, sniffs at him, and, out of nowhere, punches him hard in the face. Terror sets in. Amir, paralyzed by fear despite his far superior size and build, remains stoic. The militiamen charge at the table, smashing all of the alcohol bottles as the guests begin to tremble. “You’re going to pay for this; you’re really going to pay.” The young militiaman is not wrong : Ten minutes later and they are gone, but not empty-handed. No need to worry about Amir, they chose not to take him away with them this time, opting rather for a pile of traveler’s checks, worth a grand total of two million tomans (almost $3,000). “Bunch of oghdéi [assholes],” cries Hala. “Fucking Islamic Republic,” Omid is furious. Things could have been worse, but the apartment is trashed. The party is definitely over.

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

2 Things are necessary to Fix This

by amirparvizforsecularmonarchy on Fri Nov 11, 2011 05:20 PM PST1) People need to Rally around the Shah

2) Iran needs the opportunity to back the Shah and Succeed.

حمله! حمله به Reformist ها! !Let`s Go

Esfand AashenaThu Nov 10, 2011 06:27 AM PST

Armin Arefi "fled" to Iran? The summary above says he "fled" to Iran from France and I didn't understand it, how can he write and sell in Amazon when he is in Iran? It may be just a typo.

It seems like an interesting book but it's like watching a movie when you already know the ending.

Everything is sacred

Good Friend of Bernard Henri Lévy ( Règle Du Jeu)

by Darius Kadivar on Thu Nov 10, 2011 04:44 AM PSTHe is a regular contributor to BHL's website "La Règle Du Jeu":

Armin Arefi, Armin Arefi - La Règle du Jeu

Recommended Blogs:

WARLORD's INTELLECTUAL: BHL the Mind behind Sarkozy's Libyan Success

BHL Gathers Secular Opposition in Paris (June 11th, 2010 )

Marjane Satrapy and BHL Demonstrate in Paris