به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Reading Kafka at Harvard (4)

by Kaveh Afrasiabi

02-Dec-2008

“The effect of the place (Harvard) is singularly noble and solemn, and it is impossible to feel it without a lifting of the heart. It stands for duty and honor, it speaks of sacrifice and example.” -- Henry James, Bostonians

On January 27, 1996, the Boston Herald featured a rather unusual article that, its title alone – Harvard professor’s galpal accuses his rival of extortion – must have given serious shivers to Henry James in his grave. Times have surely changed for the worse at Harvard and, sitting in jail like one of Becket’s clowns waiting for a just and expedient end to the horror leveled on me and my family, I concentrated on the necessary antidotes that would keep me from being fated like another Joseph K. The article is worth quoting at length:

“A muddied case of alleged extortion, spiced with Middle East intrigue and Harvard prestige grew even murkier yesterday when the only real witness did not pick out the alleged bad guy in court…Shobhana Rana claims she twice turned over $250 payments of her professor-boyfriend’s cash to a death-threatening Iranian last Fall. In November statements to Harvard University police, Rana recounted one lengthy conversation with the man, the two cash drops and one surprise visit the man made to her apartment with an apparent leg-breaker…Middlesex County prosecutors planned to argue Afrasiabi was so dangerous he should not be released on bail…Afrasiabi was released on $300 cash bail on charges of threats to extort, threatening and larceny by scheme. He pleaded innocent…According to a 15-page Harvard police report, Reza Alavi called police on Nov. 9 to report $500 missing from his account. He told police Rana told him she made two withdrawals from his ATM account a month earlier to pay off the extortionist, who threatened to kill…”

“All we want from him is to go and do what he does somewhere else.” Some honor and example. These were the exact words of distinguished professor Roy Mottahedeh to my attorney, Thomas Birch, when Birch had called him and told Mottahedeh that he intended to summon him to court at my bail hearing, in late January 1996. Birch, a veteran criminal attorney and a friend of historian Howard Zinn, had stepped in to represent me after another “civil rights” attorney, Henry Owens, turned us down as we came up short for his initial demand of $40, 000.

“He’s just hiding behind a tall wall of denial. I told Mottahedeh that in case he didn’t know it, this is a free country and he can’t dictate to people what to do. And he also complained that you were going to sue him and I told him that that is what people do in this country when they feel they have been wronged,” Birch recounted the content of his conversation with the then director of Middle East Studies at Harvard -- who would soon be called a “contemptible liar,” “mean” and “nasty” by a cultural icon of America, the legendary Mike Wallace of CBS’ “60 Minutes.”

“I admire Afrasiabi. He has been wronged. The cannons of Harvard are lined up against a pea shooter,” Wallace would be quoted in the Boston papers after he testified as my character witness during the trial of Harvard defendants, including professor Mottahedeh’s ‘galpal,” Shobhana Rana, who failed to show up and testify at her trial despite a subpoena. Suffice to say here that in his in-court testimony, Wallace flatly contradicted Mottahedeh’s testimony of the day before, particularly his claim that he had never called to speak with Wallace about me. “I remember talking to him, and he had this nasty and deprecating voice, trying to make me lose whatever respect I had for Dr. Afrasiabi,” the trial record reflects.

“Did that fellow, what is his name?” “Mottahedeh.” “Right, did he have anything to do with this?” “I don’t know Mr. Wallace, but his subordinates who have accused me are.” This conversation took place on the phone, when I called Wallace from the jail and he immediately expressed his shock. There was silence for a moment and then Wallace told me that he would contact his friends in Boston media to look into it and find out what was going on. Real and serious media scrutiny is always a good antidote to a long Kafkasque nap.

“They all smelled rats from a mile away,” Wallace would tell me later, when he came to Boston and we had breakfast together at Copley Hotel, in early 1997. “It’s called criminalizing dissent, Mr. Wallace.” He readily agreed. Wallace had built a life-time reputation as an uncanny apostle of truth and would go to a great length to confirm the veracity of my allegations through his own sources. Coincidentally, the same language about rats would appear in a support letter on my behalf sent to Harvard by Murray Levin, who was a professor emeritus at Boston University and taught (political science) at Harvard Extension School. Author of several highly important books on American politics, including The Alienated Voter, professor Levin visited me in jail twice and, subsequently, would attend every single day of the jury trial in my civil rights action in the federal court.

“There is no foundation to these absurd charges against Dr. Afrasiabi and any one with the slightest intelligence reading the Harvard police report can smell rats from a mile away. It’s a classic police gaffe, a fantastic orgy of Alice-in-Wonderland meet detective Colombo, great stuff for Harvard Lampoon,” professor Levin’s letter read in part. My Kafkasque ordeal invited decipherment along such lines that resonated with the Trial’s description of a “rodent tribe.”

Several years earlier, when I worked with Wallace on a program on Iran and then on the author of Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie, Mottahedeh had gone behind my back and lie to him about me and my connection to Harvard, as a research fellow, and Wallace had trusted him in deference to his teaching post at Harvard, only later did Wallace realize the nature of Mottahedeh’s Kafkasque haunting duplicity – that had cost me my ties with “60 Minutes” for a number of years.

”This is so disappointing, and dumb. How could a Harvard professor lie like this, and to me, of all people? Did he really think he could get away with it forever?” Wallace would tell me one day, just as he was double checking all the facts through his office before sending his letter to a federal judge in Boston, exposing Mottahedeh’s lies and expressing support for me; ordinarily, had Harvard remained true to the noble spirit that James had ranted about in his novel, Bostonians, that letter alone would suffice to cause a scandalous departure of Mottahedeh. Instead, he would be fully protected by the institution, as if the university’s emblem “veritas” had become meaningless and denude of the slightest significance, only a nice façade for a perverse Kafkasque sub-universe that operated by the logic of authoritarianism, lies, and distortions, “no matter how trivial or undignified,” to borrow a line from The Trial; it seemed to breed and mutate what Herbert Marcuse refers to as “authoritarian personalities.”

I have often wondered: wouldn’t it be better if one day Harvard retrieved its youthful idealism, and was able to embrace and breed democratic personalities, instead of such Kafkasque “figures of a failure” who are so intoxicated by their feeling of power that delude themselves into thinking that they can trample on other people’s rights and, if need be, to dispossess them of their liberties in case they crossed the line with undue criticisms. Such tragic figures, alien to the spirit of tolerance and respect for the rights of other human beings, have distorted the spirit of Harvard and emasculated its once enchanted image. Indeed, the Harvardites’ numbing indifference to the irrefutable evidence of Mottahedeh’s outrageous misconduct over more than a dozen years – with respect to CBS, Oxford University (see below), my false, retaliatory arrest via his subordinates and, finally, his desperate attempt to cancel my lecture at Harvard Law School in 2006 (per subsequent information from one of the panel’s organizers) -- reflected so much about the corruption of core values at the university.

Wallace’s letter, dated June 30, 1997, reads as follows:

“Judge Joseph Tauro, Chief Justice

U.S. District Court Massachusetts

90 Devonshire Street

Boston, MA 02110

Dear Judge Tauro:

I am writing you at the suggestion of Dr. Kaveh Afrasiabi.

Dr. Afrasiabi served as a consultant to me on matters dealing with Iran, beginning in March of 1990. I had called him after reading a letter he had written to the New York Times on the subject of Iran.

After that, he cooperated with me in preparation for a program on author Salman Rushdie, object of a fatwa by the Ayatollah Khomeini; he also attended two meetings I had with Andrew Wilie, Mr. Rushdie’s literary agent.

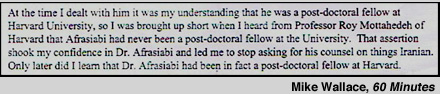

At the time I dealt with him it was my understanding that he was a post-doctoral fellow at Harvard University, so I was brought up short when I heard from Professor Roy Mottahedeh of Harvard that Afrasiabi had never been a post-doctoral fellow at the University. That assertion shook my confidence in Dr. Afrasiabi and led me to stop asking him for his counsel on things Iranian. Only later did I learn that Dr. Afrasiabi had been in fact a post-doctoral fellow at Harvard.

Since that time he has kept me informed of his various scholarly activities and it is apparent to me that he is held in high regard by various Middle Eastern Islamic scholars.

I write this solely for your information. Thank you for your attention.

Sincerely,

Mike Wallace

CBS News, 60 Minutes

Correspondent/Co-Editor”

It would be one thing if Mottahedeh’s damage to me had been limited to CBS, an important aspect of national media in America. In 1995, he repeated his ‘honorable act’ by vilifying me with the members of a fellowship at Oxford University, thus prompting me to hire an attorney in Boston area by the name of Kevin Molloy, who wrote a letter to Mottahedeh in early December 1995 and warned him of a defamation law suit if he continued smearing me in the academia. Attorney Molloy has submitted an affidavit to the federal court regarding this matter, stating:

” I, Kevin Molloy, do on oath depose and say as follows:

1. I am an attorney, admitted to practice law in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and before this federal district court;

2. In the fall of 1995 I rendered legal service to the plaintiff, Dr. Kaveh L. Afrasiabi;

3. My services included reviewing various documents provided to me by the plaintiff and advising him regarding prospective litigation against professor Roy Mottahedeh and Harvard University;

4. It was my understanding that any conversations which I had with Dr. Afrasiabi and any services and or advice which I rendered to him was in anticipation of litigation.

Sworn and submitted this third day of January, 1998,

Kevin Molloy.”

In addition to the legal remedy, I had also sought help from the Middle East Studies Association, by filing a complaint against Mottahedeh and his incessant efforts in smearing me in the academic circles, appealing to association’s ethics committee to put an end that man’s acting “like a grinch stealing my every Christmas.” I had participated at the December conference of that association in Washington, D.C., and had spoken with some members of the ethics committee including professor Banuazizi, who had promised to take up my complaint, even though as stated in the beginning chapter he would do the exact opposite by making sure that it did not come up for considerations, and later on would simply lie about his action in his deposition under oath – that was tantamount to perjury.

That aside, what attorney Molloy’s letter does not mention is that I also put him in touch with a librarian at Harvard University by the name of John Emerson, who had informed me, upon his return from a visit to Oxford, that he had heard from the fellowship committee that Mottahedeh had completely defamed me with them.

Mr. Emerson would subsequently become my material witness in a defamation law suit against Mottahedeh in a Cambridge court, after the criminal charges against me had been dropped. As expected, in retaliation, the Mottahedeh and company at Harvard would use their influence to remove Emerson from his post as the head of the Middle East Division of the Widener Library and demote him, a decent and honest man who had the courage to stand for truth no matter what the consequences; the only reason Emerson was not fired was due to their fear of legal action by him. Worse, to open a parenthesis here, they would make sure that the judge in my defamation case, a Harvard graduate who per his own admission was an active alumnus and sat on two oversight committees at Harvard including one at the Widener Library, where Emerson worked, would throw out my case on the very day slated for a jury trial. The Harvard judge would dismiss my complaint after three years of intense litigation, that included a six hour video deposition of Mr. Mottahedeh, by reversing all his evidentiary rulings of nine days earlier. I had repeatedly asked judge Hillar B. Zobel to remove himself from the case due to the conflict of interest and he refused (more on this later). In a Kafkasque universe the idea of an independent judiciary is simply a phantom.

Such is the sad state of affairs at Harvard today that rewards the authoritarian transgressors and punishes the decent and honorable ones, surely an inversion of Henry James’s laudatory “sacrifice and examples,” for what I could see in Emerson’s example was a negative example of what happens to decent Harvard employees when they put principles ahead of other interests, and that the only thing sacrificed would be honesty and integrity.

But, of course, compared to his venom against me with CBS and Oxford, Mottahedeh’s direct and indirect role in causing my false arrest and imprisonment in early 1996, a month or so after receiving attorney Molloy’s letter, meant that his earlier missteps against me would be a dress rehearsal for the much bigger blow that was meant to silence me forever.

Grappling with criminal law

“Look. These are very serious charges and you can go to jail up to six, seven, may be even ten years,” attorney Birch told me at his visit to jail, “but first thing is to get you out on a bail before the trial. This is a one-shot deal and if we lose and the judge denies you the bail, that’s it, there will be no more bail hearings and no release until the trial.”

I was petrified. “Really, and when will that be?”

”Who knows. They have quite a backlog, may be ten months from now, a year, a year and a half. I know it sounds ridiculous, but unfortunately my friend this is the law in Massachusetts.” The next morning, I impressed Birch by my knowledge of criminal law, this after taking advantage of the small law ‘library’ at the jail. I had already wetted my feet in the whirling river of law and this would be the beginning of a long ordeal, that would subsequently take me from one law library to another, consuming years of my life in my quest to learn the ropes of law and to apply it as best as I could in my quest for justice. That day, my conversation with Birch initially focused on the criminal law, Chapter 58, Section (A):

“The Commonwealth may move, based on dangerousness, for an order of pretrial detention of release on conditions for a felony offense that has an element of the offense the use, attempted use, or threatened us of physical force against the person of another.”

That law had been foisted on the state legislators some eighteen months earlier by a tough-minded republican governor almost immediately after it had been deemed unconstitutional by the justices of the state’s highest court in Aime v. Massachusetts, expressing concern that the bill did not provide procedures “designated to further the accuracy of the judicial officer’s determination of an arrestee’s dangerousness.” A self-declared “law and order” governor had, after making cosmetic modifications, re-introduced the same bill, this time ramming it through the legislator by a mock belief in its adaptability with a Supreme Court precedence, in the case of United States v. Salerno (1984).

In the Salerno case, the Supreme Court justices had veered sharply against the Constitutional amendments pertaining to bail, rationalizing the pre-trial detention of suspects as “regulatory” rather than a “punishment,” as if such semantic acrobatics would in any way diminish the pain of an unconvicted detainee who after suffering weeks or months or even years of detention would be declared innocent. What would be the remedy in those circumstances? Was the government willing to apologize or perhaps make retribution for incarcerating such an innocent person, or someone whose jail term would end up being shorter than the time he or she had already served?

But, whereas in Salerno the High Court had at least made a feeble though fundamental distinction between “serious” and “non-serious” crime, excepting the latter from the purview of pretrial detention, thus applying it to a limited category of offenses, in comparison the Massachusetts law lacked this important distinction and covered even petty burglary and certain forms of misdemeanor. Unfortunately, the Massachusetts legislators, seemingly more concerned about public safety then the constitutionality of their action, had chosen to conveniently overlook the justices’ warning in the Aime case that the “pretrial detention” law “essentially grants the judicial officer unbridled discretion to determine whether an arrested individual is dangerous.

“Very good Kaveh, I’m impressed, so that’s how you’re spending your time, other than cutting onions,” Birch reacted, suggestively as my clothes was permeated with the smell of onion after a whole day of laboring in the kitchen. I laughed and said, “thanks, I also wrote a poem last night, do you want me to read it to you?” “Sure go ahead, we should be really discussing your case and I’ve got to run to Walpole to meet with another client, but go ahead, really, if it’s short.” It was:

The Beacons on the Hill have scattered you

Like a storm ripping through the field;

You wander in your still-pulsing particles

And gather them in a vessel that lets you relax.

You see, you’re a collector.

| Recently by Kaveh Afrasiabi | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Reading Kafka at Harvard (7) | 4 | Dec 20, 2008 |

| Reading Kafka at Harvard (6) | 14 | Dec 13, 2008 |

| Reading Kafka at Harvard (5) | 16 | Dec 06, 2008 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |