به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

On the Origin and Nature of Patriarchy (5)

by Azadeh Azad

27-Feb-2011

The First Procedures for Creating Fatherhood or Social Paternity

Following the discovery of the biological paternity, men of the Bronze Age societies, who were now considered mildly superior to women, created, for the first time in history, a social unit or institution named family. To be certain of their paternity, a man had to separate his ‘’woman’’ from other men. Such certainty could not be made in matri-centric clans where women had sexual relations with a number of men. However, the first form of family was not patriarchal but based on cohabitation of a man and a women. In this pairing or cohabitating family, the bond between husband and wife was loose and non-legal, a man could guess that the children born of his partner were biologically his as well, but there was no institution of paternity and the biological fathers had no rights over the children. Matrilocality and matrilineality of the earlier times persisted in this form of marriage. These mildly male-dominated societies that were transitional between Stone Age matri-centric societies and patriarchal societies of the Ion age, could be called viriarcho-matrilineal.

History and ethnographic documentation indicate that following their awareness of their alienation from the continuity of species, men took a combination of ideological, magical and ritual procedures as well as political and economic practices with a view to becoming socially visible as perpetuators of human kind, as fathers.

To fulfil their wish to participate in the continuity of species, men of the end of the Stone Age had no other model of immediate parenthood than the one practised and offered by women, who since origins had the exclusive responsibility of the perpetuation of the species. For men, it was the only image of a sexual category able to perpetuate materially and socially the human kind. So, in order to become, like women, propagators of species, they had to imitate them at all levels, whether physiologically, economically or culturally.

1. Women have a vagina and bleed periodically. So, men began to practice the monthly subincision of their penis to pretend having a vagina and to bleed like women. For instance, among some Australians indigenous.

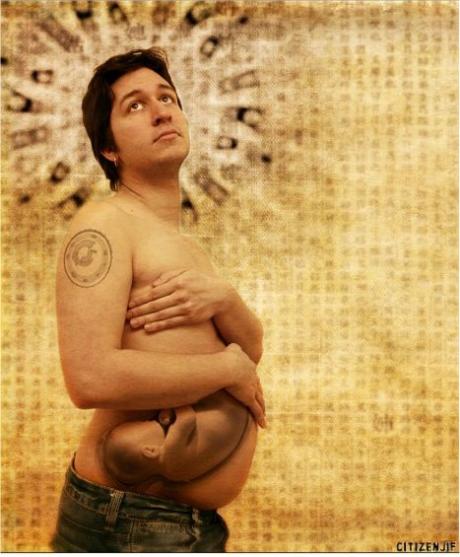

2. Women become pregnant and give birth to children. So, men began practising the rite of couvade (from French couver “to hatch.”) It is a ritual behaviour undertaken by a man during or around the birth of a child. For instance, in the Arapesh tribes of the New Guinea, a man lies on a mat in a room of his hut, moaning and clutching at his abdomen in simulated labour pain, while his wife quietly lies in another room, in actuality giving birth to the couple's child. Pretending to be able to give birth like women and asserting that during this ritual the paternal soul thus enters the body of the foetus, allow men to take the children as their own and become their socially approved fathers.

3. Women controlled the community economy by being in charge of the main activities of the provision of supplies (food gathering, hoe-agriculture, etc.) and by distributing the supplies among the members of the community (female-centric economy.) So, men decided to take control of the economy and social life like women. While before the discovery of paternity, all the important inventions and discoveries were made by women, men began exploring new domains of economic activities and became entirely responsible for the technological and scientific discoveries and inventions of the Copper Age (4000-3000 bCE) , which included animal husbandry, agriculture with plough and artificial irrigation, metallurgy, the harnessing of the plough pulled by oxen, invention of the mill with wind and with water, the sailing boat and the carriage with wheels leading to long-distance commerce (in boats and in caravans.) This revolution, besides being a response to the imperatives of the daily survival, was an economic procedure for materialising the social paternity and its principle of Potency.

4. Women took the children - they breast-fed and raised small children; guaranteed the daily survival of their children by their economic activities of providing supplies; kept their children in their locality (matrilocality) and gave them their names (matrilineality.) So, as men accumulated personal surplus and wealth (private property) following their herding, metallurgic and improved agricultural activities, they decided to buy children or spouses who would give birth to children they could have as their own.

However, the above imitative procedures were not sufficient. Men knew that in spite of the magical manipulation of their sexual organs and in spite of their big efforts of exploration and practice of new economic activities (which could be done as well by women), they could neither bring into the world a child, nor be indispensable parents for the survival and/or comfort of children, that is the species. They decided to take efficient and oppressive measures.

Reference

Bettelheim, Bruno. 1871 (1954). Les blessures symboliques, Gallimard, Paris.

Dawson, Warren.R. 1929. The Custom of Couvade, Manchester. U.K.

Eaubonne, Francoise d’. 1977. Les femmes avant le patriarcat, Payot, Paris.

Eliade, Mircea. 1977 (1956). Forgerons et alchimistes, Flammarion, Paris.

Frazer, James. 1907-1915. The Golden Bough, Vol. II, McMillan & Co, London.

Gough, Kathleen and David M. Schneider. 1961. Matrilineal Kinship, University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1929. The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia, Harcourt & Brace, New York.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1960 (1927). Sex and Repression in Savage Society, Meridian, New York.

Mead, Margaret. 1950. Male and Female, Penguin, London.

Mead, Margaret. 2001 (1935). Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies, HarperCollins Publishers, New York.

Mead, Margaret. 2001 (1928). Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization, HarperCollins, New York.

Freeman, Derek. 1983. Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth, Harvard University Press, Boston.

Meillassoux, Claude. 1979. Femmes, greniers et capitaux, Maspero, Paris.

Montagu, Ashley. 1946. Ritual Mutilation Among Primitive Peoples, Ciba Symposia, Vol. VIII: 426-433.

Roheim, Geza. 1949. The Symbolism of Subincision, The American Imago, Vol. VI:321-324.

Tabet, Paola. 1979. Les mains, les outils, les armes; L’Homme, Revue française d’anthropologie, juillet-décembre: 5-51, Mouton, Paris.

...............................................

HOME

| Recently by Azadeh Azad | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

پیروزی نسرین ستوده پس از ٤٩ روز اعتصاب غذا | 32 | Dec 04, 2012 |

نامه به سازمان عفو بین الملل برای آزادی نسرین ستوده | 1 | Nov 30, 2012 |

مفهوم سازی واژه گونه (۳-٩) | 1 | Nov 27, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |