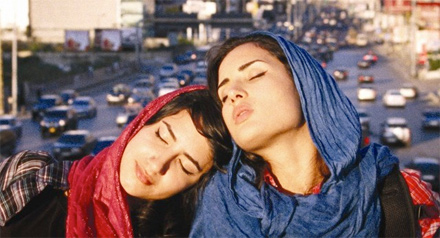

I had the opportunity to talk with director/screenwriter Maryam Keshavarz about her new film Circumstance, which won the 2011 Sundance Audience Award. Fortunately, one of the lead actors, Reza Sixo Safai, was also able to join us to add his perspective in a three-way discussion. We began with the scene where the characters are trying to dub the gay themed movie Milk to distribute in Iran:

Ari: Was this a reference to your own movie, because you are hoping Circumstance will be illegally copied and distributed in Iran? Obviously they won’t allow a story involving lesbian teenagers to be legally distributed.

Maryam: (laughs) Hoping or not, it’s going to happen. I made the Color of Love and it wasn’t allowed to be shown in Iran, but it was broadcast all through Europe, so people in Iran watched it. Interesting how stuff gets back into the country. All the underground is really into movies. I remember when I was there Brokeback Mountain was really huge. It was like, oh my god, forbidden love! It was number one. Nihilistic forbidden love is part of Iranian culture.

Reza: Yes, it will be copied. Last time I was in Iran Pearl Harbor was out and I hadn’t seen it, but everybody there had seen it and they were saying you’ve gotta see this movie.

Maryam: And we get hundreds of emails and Facebook messages from Iran. Kids are smart; they google the contacts. Especially since the trailer came out, everybody was saying we want to see this movie.

Ari: The trailer is what made me want to see the movie. Who did you imagine your audience to be? Or do directors even think that way?

Maryam: I have to say, we are selfish. For me personally—especially when I write—it’s like a cathartic experience. In fact I didn’t really want to write the script. Do you know why? Because I thought my God it would get me into trouble. I love to go back to Iran. I used to go back every year. But these characters started becoming more and more real and almost against my will they forced me to write their story. Some of the story is based on my own experience, some on the lives of people I know. The story was very different originally; it came out very self-censored because my family was in Iran and I was afraid. Everything was vague, allegorical or symbolic. It was a different story. But when I went to the Sundance class I had these great mentors and we talked about the fears of writing it the way I wanted to write it. We worked out so many of my own issues regarding the process of telling the story in my head.

I’m sure you know that when you’re a writer some things become trapped in your mind and they almost become an obsession until you write it, or in the case of a film, until you make it. And I couldn’t move on…that’s the artist impulse, you can’t move on with your life until it’s out of you. But once it is out, it no longer belongs to you. Even when I watch the film now I forget that I made it because the impulse is in the making of it. Now I feel like it belongs to the audience, and I’m one of them. You can even ask me questions like, what do you think of the film?

The process is all about what you include and don’t include. Once you get past the self-censorship, you ask yourself does this scene speak to me as someone who lives in the United States and as an Iranian? Does it work in both of the milieus that I grew up in? When it does, I feel like OK, that’s a universal thing. That’s when I know it works both for me and the audience.

Mehran’s character is somewhat based on one of my family members who is very religious. I didn’t hate him. I wanted to understand him. Maybe that’s my struggle; trying to understand people. Family members that are really Baseeji or Hezbollah, or whatever, why, why are they this way? I love them, I am close to them, but we think so differently. How did this happen? So I’m very sympathetic towards all the characters. Maybe it’s because I’m older now, have studied more Iranian history, and know more about what really happened in the revolution that I get the sense that even the most amazing people become trapped at some level. Even the strongest individuals.

Reza: What really drove me to want to do the film when I read the script was that I could sense this truth. I feel terror and I’m scared but there’s also something really beautiful about the way the family interacts with one another and how each is looking for expression of personal freedom within the family. It was really true to my experience, even though I didn’t grow up in Iran. But I related to trying to handle both cultures, having to find my own way to express my freedom in my family. My parents weren’t really used to this culture. So how do you break out of things that your family doesn’t want you to break out of?

Normally, as an actor, I concentrate on my part. But in this film I got so wrapped up in the story and the love between the women that I wanted them to be set free and live their lives they way they want to live it. That’s when I knew I have to be part of this film somehow.

Maryam: Also, the film is a love poem to this beautiful family that starts so close. How does a family this close break up, even though they really do love each other and are full of joy? It’s not like the parents are traditional and the kids are modern. At some levels the parents are probably more modern than the kids. In fact, the son is the one bringing in this idea of tradition.

In the United States you are told, don’t lie. When the teacher sends a note home…oh my God! It’s a big deal. But in Iran, especially during the war, kids were taught to lie. Because [at school] they ask you, do your parents pray at home? Do they drink? And some kids– they didn’t know–would tell the truth. And it didn’t mean that they were going to go invade your home, but it might mean that they’re going to tell you your parents are going to burn in hell. A friend of mine told me she had nightmares for the longest time about her parents burning in hell, because she told a teacher that her parents drank. The kids became so psychologically scarred that parents started teaching them not to tell the truth at school. Teaching them to lie to protect them. But what are the boundaries in teaching your kid to lie? How do you still manage to teach morality to them, when your ideals are at odds with the greater society? These are the struggles that I had to discuss in the film because the family unit is the closest most intimate thing we have. How is the family affected by these different pressures?

So many people that are not Iranian have come up to me to talk about the film. Of course, Iranians are always divided about any film about Iran, depending on so many things. An Iranian came up to me yesterday and said, “You know Maryam, I would do this film differently.” And I said, “Of course, thank you so much, very glad to meet you. You look ten years older than me, you’re a man… all these differences between us affect how as artists we would each make the film. Then I asked, “What’s your medium.” He said, “I’m a lawyer!”

We are very critical in the Iranian community. But a lot of Iranians have definitely connected to the film, older people, younger people, gay people. To me this is a test as an artist, beyond issues of politics. [Regarding the film] I met a man from DC who grew up in the Czech Republic, or someone who grew up in Cuba, or someone who grew up in Chile during the dictatorship, a black woman from Mississippi. A woman in Sundance who came up to the women actors in the bathroom was upset because she was basically homophobic and didn’t believe in the gay lifestyle. And yet she was so moved by the film that she voted for us in the Audience Award. To me this was shocking. A foreign language film about Iran? It had everything against it. I was really in shock when we won. People who don’t know anything about Iran somehow relate to the struggle. Someone asked is this film allegorical? Does it represent your country? I thought, wow, as an artist we hate to hear that. I don’t represent anything. I represent these characters. Maybe on a different day they would act differently. That’s a burden, because the US can be a very hostile place towards the Middle East—Iran especially. So you have a sense of burden of representation, and yet that would the death of our film. To represent anything.

Reza: The film is true personally in terms of characters.

Maryam: And that’s what I draw from; it’s personally true for me. As for the lawyer yesterday, of course he would make the film differently because we all speak from our experience. That can only be a good thing when there are as many stories out there as there are people. My particular story came from a sense of love and connection to Iran. The Stoning of Soraya came from a different director that didn’t have that much connection to Iran. Different director, different politics. My driving force was not politics. It was personal.

Ari: Reza, while working on the film, how did you approach the transformation of your character, Mehran, from a sensitive classical musician with a modern mindset and an inclination for partying to a devoutly Muslim character? What do you imagine happened in the drug rehab center that caused this transformation?

Reza: One thing that was important to me with Mehran was to make him a human being. I think it’s easy to read the script and just say, oh this is the antagonist; he’s the bad guy.

Maraym: when I auditioned actors, 99.9 percent read Mehran as the bad guy, but when Reza auditioned I just wanted to give him a hug. I felt so tender towards the Mehran that Reza portrayed.

Reza: With Mehran’s drug addiction, the biggest feeling that comes out for me is being trapped—not having any options. He’s not working, nothing is happening for him. So when he comes back from rehab, he doesn’t make any conscious decisions; he just goes towards anything that he thinks might be an answer. When he goes to the mosque, he’s looking for a place where he can get quiet, but even there he can’t run away from his past. A beggar approaches him in the mosque and Mehran has so much self-hatred, shame and guilt about the situation he’s created that he’s sure the helpless beggar is him. I think he wants to regain some power ultimately, which is why he embodies and takes on religion. He sees the man [the religious community leader] he meets in the mosque as a surrogate father because he has issues with his own father as he struggles to have an independent identity as a man. I also made a choice that because of the themes in the movie in terms of sexuality, in terms of drugs, to imagine that Mehran during his drug use was involved with the guy that he beats up after he gets out of rehab. This has nothing to do with what is explicitly in the film, its just part of the back-story an actor imagines for himself. Something happened between the two characters.

Maryam: That’s waaay deep underneath!

Reza: There’s something going on there.

Ari: Actually I strongly sensed it in the scene. You don’t beat someone up that viciously unless there’s something going on.

Reza: And again, Mehran is realy beating himself up, in a way. We may mostly notice Mehran’s becoming religious, but there is much more going on with him. For example, his love for Shirin is real.

Maraym: Yes, he wants to save her.

Reza: He wants to save her, and of course he has no idea that this is just killing her. I find the idea of loving someone who can’t love you back tragic.

Ari: At one point Mehran shows Shirin that he’s vulnerable to her. He asks, “Why am I not enough for you?” There’s an old adage to the effect that women don’t want to hear I love you; they want to hear I need you. What’s a behind the scene story to that exchange?

Maraym: That’s a very complex scene. Even to shoot, emotionally. And the audience also read it very differently. At one level Mehran rapes Shirin, but at the same time Shirin realizes that he is under her power at some level, even though she is the rape victim. He loves her, and she can hold back love or give it. She sees his humanity. In any culture men are required to be so macho; you expect them to be the powerful one. But reality is that they are just as vulnerable, they just don’t have the space to cry and show emotion. He has to break down his character to the point of tears for her to see him as a human being. The scene is rife with complexity. What a marriage is, power in a marriage, the idea of forgiveness in a marriage, the issue of sexual boundaries in a marriage… it was a complex and difficult scene.

Reza: In all these transitions, you find out what Mehran is trying to do is to be heard and seen.

Maryam: There’s the power aspect. He wants to control the family. But he is also saying, I’m a human being. He is the jailer. He is the one that has incarcerated everyone in the family. He has trapped the whole family. But he’s also inside the bars himself, just as much a victim as the rest.

Reza: And when he is offered money [for fixing the mosque’s PA system] he is not happy about taking it. When he finally accepts, the first thing he does is buy his sister a birthday present — three weeks late. But the gift is not well received. When he buys land to build a house, his parents just walk away. And he wonders when am I going to be enough? In a situation like that, with limited options, its really hard to resist anything that gives you sense of self worth.

Maryam: There’s also the frustration of the rest of the family. They trusted Mehran and he broke their trust. Mehran and his sister, Atefeh, were best friends, but he has violated their friendship [by forcing Atefeh’s lover, Shirin, into marrying him]. Atefeh tries to reach out…there’s so much politics in family relationships. Siblings trying to win the affection of the parents, vying to be seen, complexities which are never the same, always shifting. [smiles] I have severeal brothers, one of them the same age as me.

Ari: I saw a video of the three actors talking about the Maryam…

Maryam: [laughs] It’s not true!

Ari: One of the actors said, “Maryam knows exactly what she wants.” And I thought to myself, is that actor complaining? Maraym, what is your approach to the actors adding to the character, bringing in aspects you hadn’t imagined?

Maryam: We took a long time to develop the characters, like a year. I’m very open to talking with the actors about their characters’ back stories. But there are times when you also have to stand up and say I know exactly what this scene is. And there’ll be a fight. For example in the scene where Mehran tell her sister “your hands are dirty.”–the idea that her hands are najes. The actress wanted to start off the whole scene angry. Just various levels of anger. And I said “No,” you have start by joking with him when you reply; she doesn’t think he’s serious. But when she finds out he really means it, that’s when the shock and anger come in. When you play it with the same emotion, the insult doesn’t stab. We actually had a big fight about it; she was saying, “I know the character.”

Finally there’s a moment when you have to say, OK we’ll do it both ways but trust me I know what will work in terms of this character. The girls had never acted; this was their first film. But it worked for us because we trusted each other. I don’t think we could have done what we did if we didn’t trust each other. I love these characters; they love these characters. They knew that I’m not just doing this for some political reason. They knew that I had a lot at stake, that I have family in Iran, love Iran, have always focused on Iran not just in film but in my education too, so they trusted that we all wanted to make the best film.

***

True to Persian custom Maryam, Reza, and I had a doorway parting conversation. We continued about the stresses of making the film in Lebanon. Though they had permission to film, authorities could walk in at any time and ruin the mood—or worse. Imagining the Lebanese authorities walking in on the Milk dubbing scene where the actors were making loud gay sex noises into the microphone made me crack up. Maryam and Reza appeared less amused. Must have been rough, despite all the fun they had making the film—and despite the fact that Circumstance had beaten the odds with sheer talent to win the internationally coveted Sundance Audience Award.