به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

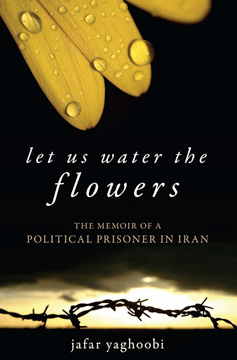

Let Us Water the Flowers

by Jafar Yaghoobi

17-Apr-2011

Let Us Water the Flowers

The Memoir of a Political Prisoner in Iran

By Jafar Yaghoobi

Prometheus Books, 2011

EXCERPT

It was late afternoon when a guard took me out of the cell and put me in a small line of prisoners. It was terrifying not to know what might happen next. In my heart and mind, I said good-bye to my loved ones. I truly thought it was the end of the road for us right then and there, given that after a long session of questioning we were lined up toward the amphitheater. The guards ordered everyone to grab the shirt of the person in front of him, then led the line forward. Were we being taken to the amphitheater to be hanged? Did they have something else planned for us? Maybe we were going back to Ward 8?

As soon as they led us into the amphitheater, I closed my eyes under the blindfold, with only the last vision of my wife and daughter in my mind, and I prepared to die. But we went through the amphitheater and soon emerged from the other end. We were suddenly outside of the building and in the compound grounds. I then thought they were going to hang us in the warehouse. The guards ordered us to jog. We went around the main prison building from the northwest toward the southwest. We were led into the building again from another entrance and were taken up to a solitary ward on the second floor. Guards pushed each of us into an empty cell.

I stood there, stunned motionless. I was relieved not to have been immediately hanged, but horrified, knowing where they had brought us. I removed my blindfold and started examining the cell. Through the metal window shades I saw the adjacent building, the prison clinic, and then I was certain that we were in the small solitary Ward 10, the so-called terminal solitary. In the southern half of the prison, where the Mojahedin prisoners had been kept before, Wards 2 and 10 had now been turned into terminals, where prisoners were processed during the massacre.

The cells had absolutely nothing in them. We were not even given the ugly prison blankets. There was only a small built-in metal toilet and sink in the cell. This indicated to me that they were not planning to keep us there long. Suddenly the cell door opened and two guards jumped in and started beating me mercilessly, apparently because I had removed my blindfold in the cell without permission.

That first night, an official moved me into a cell in the southern side of the ward. Later, I heard footsteps in the ward, and soon a few cell doors started opening. Minutes later the absolute silence of the ward was broken by the sound of flogging and the screams of prisoners. It seemed that they were lashing those prisoners either in the hallway or in the zirehasht of the ward. Later, I figured out that the victims were the last few secular leftist prisoners who had still not agreed to pray and therefore were being lashed several times daily. The floggings continued for the next couple of days, but gradually the number of people being lashed decreased until there was only one prisoner still being beaten; he, too, must have given in, because finally the flogging stopped completely.

The first night there, I was not given any food. I paced the cell constantly, pondering my fate. I was anxious and jumpy, and I thought I had to stay awake in case they came to take me for hanging. My terror of losing my life, combined with the eerie silence of the ward, was maddening. In the morning I felt like a zombie. Because of the constant stress of the last few days, and having had very little food and sleep, I had started losing weight rapidly.

I was experiencing a strange mental condition. On the one hand, I thought I had to stay awake and alert. On the other hand, not enough rest made me weak, slow, and tired. I could see the contradiction, but I was not able to do anything about it. There was nothing in the cell to keep me busy, so I paced the cell and pondered, arguing with myself, analyzing nonstop, and strategizing about different scenarios. Food and sleep—regular prison pleasures—held no appeal for me anymore.

The main struggle in my mind was about what I should do if the authorities demanded things that I could not morally accept to save my life. My interpretation of the situation was that we were in line for the final judgment. We were death-row prisoners now. Within a day or two, after I resolved the issue of life and death for myself, and after I developed clear criteria about what to do if faced with such a dilemma, I was a bit relieved. But still, I was so anxious that I jumped at any noise. I certainly was ready to have it over and done with. Human beings are interesting creatures. We can and do adapt to unimaginable conditions and circumstances as long as they do not physically destroy us. After a few days, I started to get used to living under these most dangerous and stressful conditions. I gradually calmed down. I had to overcome my internal struggle to be able to interact with my surroundings.

AUTHOR

Jafar Yaghoobi, PhD, was released from prison in 1989 and subsequently escaped to Turkey before joining his wife and daughter in Germany. After settling in the United States, he worked as a genetics research scientist in the Department of Nematology and Plant Pathology at the University of California, Davis, until his retirement in 2005. Since his retirement he has been active in bringing attention to human rights abuses in Iran.

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |

Good to know what to do if caught up as a political prisoner.

by Esfand Aashena on Mon Apr 18, 2011 06:46 AM PDTEverything is sacred