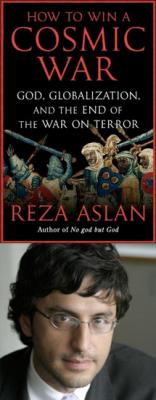

How to Win a Cosmic War

God, Globalization, and the End of the War on Terror

by Reza Aslan

REVIEW

How to Win a Cosmic War is Dr. Reza Aslan’s newly released book after the successful publication of his first. In this book, he offers a detailed examination of Jehadisim and Islamism as two widespread Islamic movements with different ideologies and agendas. Although religious fanaticism has been blamed by the majority of observers for the violence and the deadly attacks against the U.S. and other Western countries, Dr. Aslan tries to defend religion as a decisive force that, if utilized prudently, can play a constructive role in mobilizing the masses toward a peaceful emancipative cause. No religion, including the religion of Islam, promotes violence and sanctions unjustified attacks against innocent people, “… no religion is inherently violent or peaceful; people are violent or peaceful” the author says. Throughout the book, Reza explains how both the ill-conceived doctrine of the Bush administration and the misguided beliefs of the organized Jihadist groups like Al-Qaeda have changed the nature of the war on terrorism and transformed it into a cosmic war, a divine struggle with an important mission that is neither political nor economic; it is rather the fulfillment of a much bigger spiritual cause. “Once cast as a ‘cosmic war,’ a conflict conveys a sense of importance and destiny to those who find the modern world to be stifling, chaotic and dangerously out of control” one researcher says. A war that cannot be won through military might should have not been waged to begin with. According to Dr. Aslan, the best way to win a cosmic fight is to “refuse to fight in it.”

Throughout his book, the author keeps reminding us of the unavoidability of religious movements, especially in many Muslim countries, as a legitimate development that, if given the opportunity, may evolve into a democratic and responsible political force or governing body as we have seen in Turkey. The greatest threat to world peace, he believes, does not come from Islamic movements but from “religious trans-nationalist movements” best typified by the nascent borderless movement branded in the Unite States as Jihadism.

In his book, the author carefully examines the historical roots of the religious movements in different Muslim countries, especially in Egypt, and the events that have led to the rise and the demise of many such movements. His meticulous research on the theoretical foundation of such movements is indeed scholarly, revealing, and enlightening. In particular, he tries to explain why the two Islamic movements, Islamism and Jihadism, once close cousins, have split into two separate, opposing, or even hostile, movements with different worldviews. He writes that today “Islamism remains a nationalist ideology, whereas, most Jihadists want to erase all borders” and become global. In a nutshell, Islamism, like Harakat al-Muqāwamat al-Islāmiyyah, Hamas in Gaza is a national movement that draws its strength from the suffering of Moslem Palestinians and their unbearable living conditions under the Israeli occupation. In other words, the plight of Palestinian people has become a bonding factor, a drive to the creation of Hamas and similarly the Hezbollah. Jihadist, on the other hand, is a global movement that does not recognize any boundaries. It “seeks a deterritorialized Islam” according to the author, thus launching a cosmic war which “… in its simplest expression refers to the belief that God is actively engaged in human conflicts on behalf of one side against the other.” And, it is because of this divine involvement that ultimate victory is presumably guaranteed for the Jihadists.

The treatment of Muslims by the Bush administration, the war with Iraq and Afghanistan, and the doctrine of preemptive strike against Islamic countries have given the Jihadists the necessary grounds to represent themselves as the sole defender of the faith against the forces of those who contemplate the obliteration of Islam, the Crusaders in particular, thus justifying their destructive campaign against the U.S. and its allies. “There is no doubt that the policies of the Bush administration have only strengthened Jihadism and increased its appeal, particularly among Muslim youth.” However, the author expects that with a new administration in power and our new president “who finally understands that the only way to win a cosmic war is to refuse to fight in one” there is a hope that “the ideological conflicts against militant forces in the Muslim world” will be reformulated “not as a cosmic war between good and evil but as an earthy contest between the advocates of freedom and the agents of oppression.”

In so far as the war on terrorism is fought as a cosmic war, it cannot be won through conventional warfare because there are no specific enemies with a clear agenda, no one knows what the Jihadists want and what they ultimately try to achieve. “There is no central front to the war on terror because their (Jihadists’) identity cannot be centered on any territorial boundaries” and “indeed, it is their utter lack of interest in achieving any kind of earthy victory that makes them such a distinct and appealing force in the Muslim world.” Furthermore, Jihadism is a social movement as the author emphasizes repeatedly. “Yet whatever military success the United States and its allies have had in disturbing al-Qaida’s operations and destroying its cells have been hampered by their utter failure to confront the Global Jihadism as a social movement.” Accordingly, success in the war on terrorism “requires a deeper understanding of social, political, and economic forces that have made Global Jihadism such an appealing phenomenon, particularly to Muslim Youth.” “It is a battle that will be waged not against men with guns but against boys with computers, a battle that can be won not with bullets and bombs but with words and ideas.”

Dr. Aslan’s rigorous examination of the key factors that transform young men into zealous Muslims willing to sacrifice their lives, determined to challenge the existing world order, and serving as the conduit for horrific attacks against innocent human beings helps us to better understand Jihadism and why it should be considered a social movement. The author argues that it is the demonization of Muslims in many Western countries like the UK that changed otherwise peaceful Muslims like Hasib Mir Hussain – one of the four terrorists who carried out a suicide attack by detonating a bomb on a bus that exploded in Tavistock Square in London killing 13 including himself – into violent Jihadists. “It may have been anger and humiliation and a deep-seated feeling of inequality that led Hussain to Global Jihadism” he declares.

Pivotal to the central theme of his book is the argument that “in this new, emerging century, as the boundaries between religion and politics are, in part of the world, becoming increasingly blurred, we can no longer afford to view the religious movements as inherently different from any other groups of individuals who have linked their individual identities together with the purpose of challenging the society.” He continues to say: “The truth is that religion has certain qualities that make it a particularly useful tool for promoting social movement activism.” Religion can provide unity among people who belong to different ethnicities, cultures, languages, etc. “most significantly, religion’s ability to sanction violence, to declare it permissible and just to place it within the cosmic framework of order versus chaos, good versus evil, is indispensable to the success of social movement.”

He seems to suggest that while the fear of Jihadism is warranted, the fear of Islamism is overblown. Islam, like any other religions, is not inherently violent. It is the humiliation and the hectoring of young Muslims that adds fuel to the fire of violence and not the teachings of Islam per se. Thus, terrorism is a symptom of much deeper problems that drive some Muslims into despair and anger and into taking revenge out of desperation. We want to make sure the sources of terrorism do not remain undetected or untreated. Imposition and the use of force make Jihadists resentful, defensive, and more determined.

In the final Chapter of his book, Reza Aslan presents his “Middle Ground” viewpoint, his optimistic argument that the Islamist groups if allowed to take active part in social and political processes “albeit within certain accepted parameters” not only soften their otherwise uncompromising views but “they can evolve into responsible political actors committed to democratic ideals of human rights, women’s rights, government accountability, the rule of law, pluralism, and judicial reform.” Doing so also weakens the support for the extremists according to the author. Therefore, given the chance to choose between bad and worse, “Islamism is the preferable middle ground. It may in fact be the antidote to Jihadism.”